Other than a certain week in August whose name we shall not speak here, 2013 was a great year for both shark science and the communication of that shark science. There were many important and fascinating discoveries, and many of the world’s top media outlets covered them. Presented here is a list of 13 amazing scientific discoveries made in 2013, in no particular ranking order. To make the list, research must have been published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal in 2013, and someone else other than me must have also thought it was awesome (i.e. it received mainstream media or blog coverage). In the interest of objectivity, I did not include any papers that I or my lab were directly involved with. Whenever possible, I’ve linked to an accessible version of the paper.

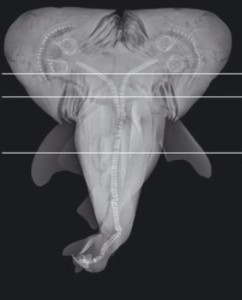

1) A two-headed bull shark!

Brief description: Researchers presented the first case of a bull shark embryo with 2 heads (the mother was caught by a Florida fishermen). In response to the most common question I received about this study, no, this animal would not have survived to adulthood. While this is a cool discovery, the broader significance is somewhat minimal. As I told science writer Douglas Main in an interview about a similar study, “There have been a number of reports of deformed shark and ray embryos in recent years— two heads, one eye, etc. There’s no evidence to suggest these defects represent a new phenomenon or that they are harmful to shark populations as a whole.”

Media coverage highlights: A figure from this study was named one of the coolest science photos of the year by the International Science Times. It was also covered by National Geographic, the Guardian, and TIME magazine.

Read More “13 amazing things scientists discovered about sharks in 2013” »