In June of 2014, almost 400 of the world’s top shark researchers gathered in Durban, South Africa for the 2nd Sharks International conference. The four keynote presentations have just been put online.

In June of 2014, almost 400 of the world’s top shark researchers gathered in Durban, South Africa for the 2nd Sharks International conference. The four keynote presentations have just been put online.

Beyond Jaws: Rediscovering the “lost sharks” of South Africa

Dave Ebert, Moss Landing Marine Laboratory

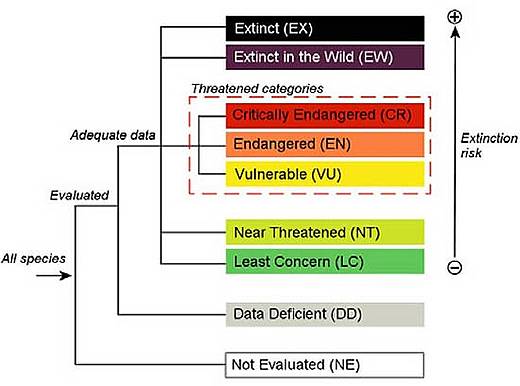

Biography:Dave Ebert earned his Masters Degree at Moss Landing Marine Labs and his Ph.D. at Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa. He is currently the Program Director for the Pacific Shark Research Center, a research faculty member at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, and an honorary research associate for the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity and the California Academy of Sciences Department of Ichthyology. He has been researching chondrichthyans around the world for nearly three decades, focusing his research on the biology, ecology and systematics of this enigmatic fish group. He has authored 13 books, including a popular field guide to the sharks of the world and most recently he revised the Food and Agriculture Organization’s Catalogue of Sharks of the World. He has published over 300 scientific papers and book chapters, and contributed approximately 100 IUCN Shark Specialist Group Red List species assessments. Dave is regional co-Chair of the IUCN Northeast Pacific Regional Shark Specialist Group, Vice Chair for taxonomy, and a member of the American Elasmobranch Society and Oceania Chondrichthyan Society. He has supervised more than 30 graduate students, and enjoys mentoring and helping develop aspiring marine biologists.

Biography:Dave Ebert earned his Masters Degree at Moss Landing Marine Labs and his Ph.D. at Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa. He is currently the Program Director for the Pacific Shark Research Center, a research faculty member at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, and an honorary research associate for the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity and the California Academy of Sciences Department of Ichthyology. He has been researching chondrichthyans around the world for nearly three decades, focusing his research on the biology, ecology and systematics of this enigmatic fish group. He has authored 13 books, including a popular field guide to the sharks of the world and most recently he revised the Food and Agriculture Organization’s Catalogue of Sharks of the World. He has published over 300 scientific papers and book chapters, and contributed approximately 100 IUCN Shark Specialist Group Red List species assessments. Dave is regional co-Chair of the IUCN Northeast Pacific Regional Shark Specialist Group, Vice Chair for taxonomy, and a member of the American Elasmobranch Society and Oceania Chondrichthyan Society. He has supervised more than 30 graduate students, and enjoys mentoring and helping develop aspiring marine biologists.

Read More “Watch the Sharks International 2014 Keynote Presentations!” »