Every scientist I work with spends most of the day communicating, whether that’s preparing grants, manuscripts, theses, outreach talks, emails to colleagues/students… the list goes on. However, most of these outlets share fairly strict formatting rules. Grants comes with pages of guidelines. Talks have defined who I am, what I did, found, next, thank you slide. While this sterile approach is arguably fundamental to science’s critical tenant of replication, it makes for terrible communication.

Author: Michelle Jewell

Many friendships in the 90s were built or lost over who got to select their Mario Kart character first because character selection largely determined whether or not you would win. SNES Mario Kart designers tried to correct this by crafting tracks that favored one character over others, guaranteeing a win on at least one race. Bowser’s fast top speed and drifting skills made them the best suited character for Bowser Castle’s sharp turns and straightaways. The icy pools of Vanilla Lake smiled upon Koopa Troopa and Toad’s tight handling and minimal drift, but that was arguably the only track they could dominate.

Now imagine another version of Mario Kart, but instead of a variety of different tracks that celebrate different strengths, every track was built by Mario. With Mario as an architect, it’s highly likely that every track would favor his particular set of (minimal) strengths. This would give the non-Mario players an unintended disadvantage since they would never get a chance to excel with their diverse skills, and the majority of races would consequently be won by Marios. In many places, this is the current state of academia.

Can you remember how young you were when you were first taught stop, drop, and roll? How about turn around, don’t drown? Slogans are abridged stories that fulfill our human need to convey information quickly and memorably. Their uses range from social connection, cooperation, and informing cohorts of risk. Sayings like the above are effective … Read More “Worldwide SciComm Challenge: #SharkSafetySlogan” »

I have had the pleasure of working communications roles in several industries over the years. During this time, I’ve seen the rise of a dubious campaign metric commonly referred to as “Stop the Scroll” (or “Swipe”). This metric has conscientious roots. Online communications strategists have less than a second to grab a potential donor, stakeholder, or client’s attention. Good strategists have read Craig McClain’s paper, as a great visual will make your thumb quiver before scrolling on to a video of dogs doing literally anything. In this light, stop the scroll seems like a pretty good metric for individual post efficacy. Time is the currency of experience, after all.

Can we count the seconds people spend learning untrue facts as progress towards our campaign? Or change the campaign goals to justify a resource-heavy shit post?

There is controversy whenever a human creates a close interaction with a wild animal. Those arguing in favour of the human’s behavior inevitably settle on the argument that if the animal didn’t like it, the animal would have bit them or exhibited some sudden reaction to the human. People who propose this argument have a … Read More “Why I don’t bite everyone that stresses me out: The cost-benefit analysis of predators” »

Note: This post has been updated on 18 September 2017.

Friends, Researchers, Countrywomen, lend me your ears!

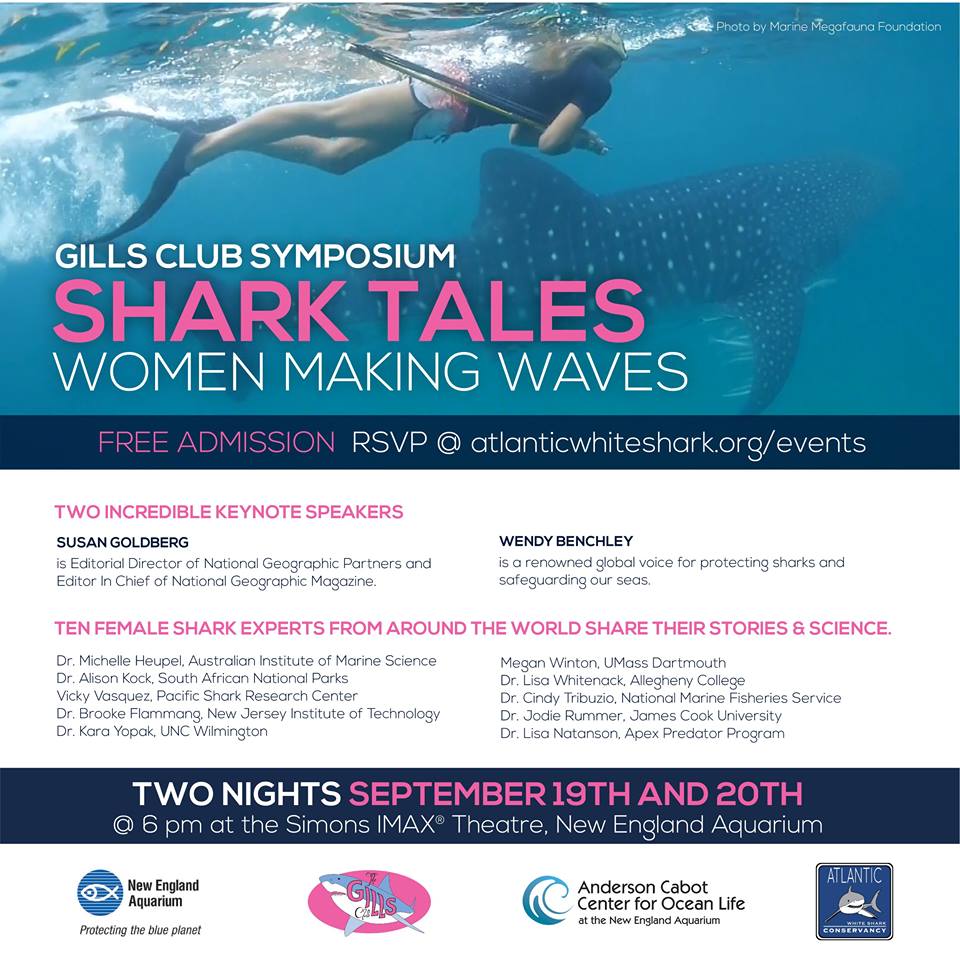

The Atlantic White Shark Conservancy and New England Aquarium are hosting a completely free two-day event, 19-20 September, featuring an amazing line-up of shark scientists and enthusiasts, including:

Keynote Speakers:

Susan Goldberg – Editor in Chief of National Geographic Magazine

Wendy Benchley – Renowned global voice for shark protection and co-founder of the prestigious Peter Benchley Ocean Awards.

Gills Club Science Team Speakers:

Dr. Michelle Heupel – Australian Institute of Marine Science

Dr. Alison Kock – South African National Parks

A shortened – and less ribald – version of this post was published 24-07-2017 in the International Business Times.

Ah, the transition from middle school to high school… the one part of adolescence no one reminisces about fondly. It’s the time in our lives where mental and physical changes happen at pace without any apparent continuity, and we feel compelled to blend in. This is the same time when most young girls’ interest in STEM stops, and in my educator/zoologist opinion, these events are related.

What does our culture gear teenage girls to prioritize? Making varsity teams, growing boobs to the correct size and at the correct time, and completing enough social jostling to earn the superhuman prom date. Most of the STEM-geared young girls I have worked with couldn’t care less about the above – but the attitude of their peers changes by the end of 8th grade.

Students of both sexes in 6th grade will happily discuss how rainbows are made and share their mutual wonder if the natural world, but those conversations quickly become “immature” when the puberty plague takes hold. It’s also in 8th grade when boys enter a race to the bottom of inappropriate jokes fueled by mutual insecurities. Suddenly, STEM-interested pupils find that their friends are segregating, fashion forward girls to one side and crude boys to the other, leaving a handful who want to discuss the space/time continuum floundering somewhere in the middle.

Then, regardless of where you sit on the social divide, hormones kick in. This critical time is when young people figure out how to create partnerships, what constitutes a good or bad relationship, and the physics of copulation. In addition to this, obtaining a socially higher-ranking partner becomes an unconscious priority. Guess what most young men think is unattractive in women? Intelligence (unless you’re beautiful enough to compensate). YOU READ THAT CORRECTLY.

Read More “What makes high school girls love sharks but avoid science” »

Many aspects of science-ing are not explicitly taught, and scientists become accustomed to mastering the deep end. While this tactic can make you stronger, there are situations where the deep end is a vulnerable place where nasty critters are very happy to take advantage.

One such area? How to handle being contacted by “producers.” In my experience, for every 1 exceptional producer you speak with, you will be contacted by at least 4 scammers. Scam producers will particularly target naïve early-career scientists, just like white sharks and seal pups. In light of this week, I’ve put together a guide to aid YOY scientists rising in the ranks of popularity and make the deep end a little safer. Here are 13 ways to spot scam shark documentary producers, with a few 🚩🚩:

Overall job satisfaction in academia has been steadily declining for many independent reasons I won’t get into here (see Nature 1 and 2). However, we do need to accept some ownership for this dissatisfaction. Our expectations and goal posts are understandable set very high. Indeed for many of us, our impossible standards and stubborn determination are the only reasons we got this far, so it can be painful – nigh impossible – for those who are hardwired to overachieve to step back and be happy with the big picture. We need to, because the stakes are as high as health, sanity, and relationships.

This inspired me to develop a new set of milestones to measure our academic careers by. Not only for our sanity, but especially for those younger scientists and students still fighting their way up the ladder.

Here are 12 new milestones of achievement I recommend we measure our career success by:

If you plan to give up one thing in 2017, make it the social media trap that so many NPOs/NGOs/individuals have fallen into. We need more organizations and individuals talking about what they are doing in the real world and less that just talk. We going to need that now more than ever.

Read More “We can’t afford to substitute genuine outreach with social media metrics” »