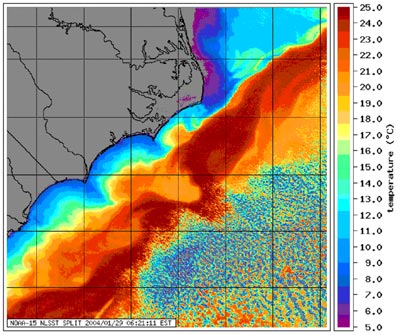

North Carolina is well known for both its distinctive barrier islands (making Pamlico Sound the largest lagoon in the U.S.) and highly productive fisheries. Both of these features exist in large part because North Carolina sits that the point where two of the largest ocean currents in the Atlantic meet. From the north, the Labrador Current meanders from the Arctic Circle along the Canadian, New England, and Mid-Atlantic shorelines and crashes into the Gulf Stream at Cape Hatteras, deflecting this warm current off its own shore-hugging course from the south and out across the Atlantic Ocean. Aside from literally defining the shape of the Outer Banks, the collision zone represents the boundary between temperate waters to the north and subtropical waters to the south. This presence of this border means that, depending on the time of year and local weather conditions, you can catch just about any marine fish native to the Northwest Atlantic Ocean off of the Outer Banks.

Environmental fronts, areas where environmental factors suddenly change, are great places for marine predators. This particular spot has proven important to the shark research I’ve been working on, so when I was invited by the Cape Hatteras National Seashore to give two talks in the Outer Banks during Spring Break, I decided that part of my trip would be to see the currents collide myself. So after giving the talks, I took advantage of the unseasonably warm weather to dip my toes in the confluence of the Labrador Current and Gulf Stream.

One of the jobs of a scientist is to reduce natural phenomena down to the base elements that make them work. This may seem like it would strip the wonder from a place like Cape Hatteras, but knowing how this place works only served to make it more impressive to me. Knowing why the Outer Banks come to a point in this place didn’t diminish it, and in fact it was totally worth the half-mile walk from the parking lot. It seemed important that the first time I put a foot in the ocean in 2015 would be here.

Of course, this was the second week of March. It was pretty damn cold.

I had a similar feeling once in college, when I walked out to the tip of Point Arena, where the San Andreas Fault heads out to sea. Standing there at the intersection of the North American and Pacific tectonic plates, and the cliff between the land and sea…a unique sensation, which was made even more impressive by my knowledge of the geology around me.