Today is Hagfish Day! Who knew?

What is a hagfish?

Hagfish are primitive eel-like chordates make famous for their relative unattractiveness*, profuse production of slime, and charismatic ability to tie themselves in knots. They are perhaps the only ‘fish’ that possesses a skull, but no vertebral column. But the question “What is a hagfish?” goes much deeper than that and it’s answer is fundamental to the evolution of vertebrates and, ultimately, us.

The National Academy of Sciences must have known today is Hagfish Day too, because yesterday afternoon they published online microRNAs reveal the interrelationships of hagfish, lampreys, and gnathostomes and the nature of the ancestral vertebrate. You see, hagfish have a problem, and it’s much bigger than too much slime blocking the gills. For most of their history, no one knew quite what to do with them.

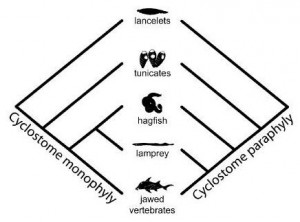

There are two opposing views of hagfish evolution. On one side, molecular evidence suggests that hagfish are most closely related to lampreys, a fair enough assumption and one that fits comfortably into our framework of vertebrate evolution. On the other side, morphology suggests that hagfish and lampreys were paraphyletic – that is, they aren’t most closely related to each other – and that lampreys and jawed vertebrates were BPF (best phylogenetic friends). The problem with the second option is that it would mean that the convergent evolution of hagfish and lampreys, or the subsequent degeneration of both groups into their current complementary forms would represent the single most exceptional event in all of evolution. We’d basically be talking about the transition from tunicate to vermiform ‘fish’ happening twice.

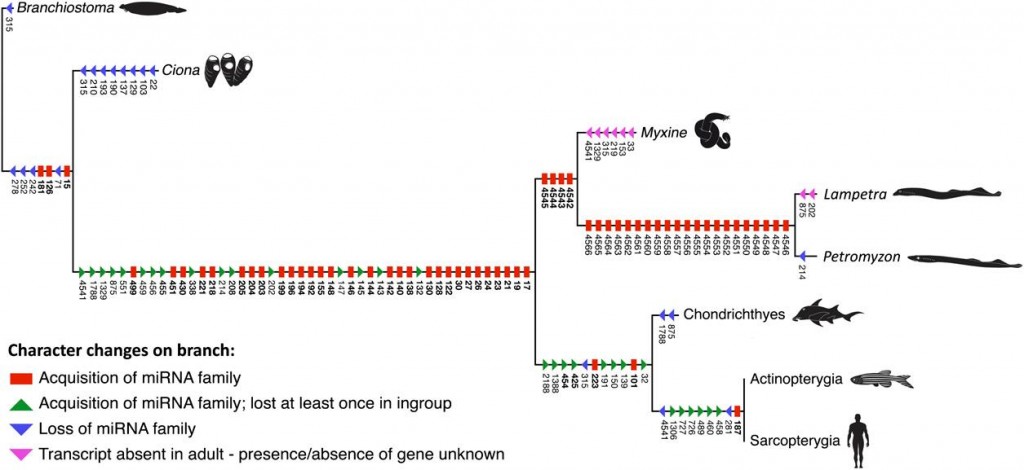

So Heimberg et al. set out to solve this puzzle using microRNA’s. microRNA’s are small bits of RNA that control gene expression in certain parts of an organism. They can essentially be treated much like morphological traits – the more microRNA’s two species have in common, the more closely related they are. By building the most parsimonious tree of microRNA acquisition and loss, they reconstructed a basic picture of early vertebrate evolution.

Not surprisingly this new analysis agreed with the morphology. Hagfish and lampreys are more closely related to each other than to anything else. This leaves us with a new problem though, because we still do not have a good picture of the common ancestor of all vertebrates, the lineage that unites hagfish, lampreys, and Homo sapiens into a single taxon. Somewhere between Tunicata and Cyclostomata we acquired huge numbers of regulatory genes and experienced a massive expansion of our genome. The mystery of cyclostome monophyly may be solved, but the transition to vertebrate body plan remains unresolved.

~Southern Fried Scientist

For a more, see Wired Science: Hagfish Analysis Opens Major Gaps in Tree of Life

*I think they’re beautiful

Update: Tree!

Heimberg, A., Cowper-Sal{middle dot}lari, R., Semon, M., Donoghue, P., & Peterson, K. (2010). microRNAs reveal the interrelationships of hagfish, lampreys, and gnathostomes and the nature of the ancestral vertebrate Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1010350107

Happy hagfish day!

I haven’t been able to access the paper, but I heard a talk by Kevin Peterson about this and related topics a few days ago and got to talk to him afterwards…

The other way around: most of the morphological evidence suggests, if taken literally, that lampreys and jawed vertebrates are sister-groups (if we ignore all except the living), which means that “Cyclostomata” is paraphyletic (it contains a common ancestor and some but not all of its descendants). The molecular evidence, on the other hand, has consistently supported cyclostome monophyly.

It may be that the vertebrate characteristics hagfish lack were secondarily lost as an adaptation to life on dark sea floors.

Not at all. The tunicates are not our ancestors. They sit at the end of their own long branch, as your figure correctly shows. The question is whether 1) things like the round mouth with horny “teeth” in it are normal for vertebrates and secondarily lost by the jawed vertebrates, or 2) they are unique to Cyclostomata, and the hagfish lost things like vertebrae and eye lenses secondarily. Either way, the long, wormlike body shape is normal for vertebrates and was modified by the jawed vertebrates – as long as you kindly ignore all fossils, at least.

Unless one of them has lost a lot of microRNAs. The authors say that this almost never happens, but I wonder if their method of analysis systematically underestimates how often it happens.

Homo sapiens.

Really. It’s not English. The -s is not a plural ending. (In fact, it’s the nominative singular ending. Latin is a bit weird that way. The plural would be sapientes, except that species names are singular-only.)

A single taxon. Two taxa. Greek. (Well, fake Greek, but never mind.)

Somewhere between our last common ancestor with the tunicates and our last common ancestor with the cyclostomes a genome duplication happened, or two. This is also suggested by independent evidence from other regions of the genome, such as the number of Hox genes.

This only means that the various hagfish species share a common ancestor that wasn’t also an ancestor of anything that’s not a hagfish. That’s uncontroversial. You probably mean “cyclostome monophyly”.

Typos fixed, thanks! The dangers of writing at 2 in the morning.

Wow, yep, totally got that backwards. Thanks for catching that.

Absolutely.

Sure, I could have been move precise in saying that the development of the vermiform body from the common ancestor of vertebrates and tunicates occurring twice would be exceptional. And it would be exceptional. From the article: “Alternatively, if the molecular phylogenies are correct, then it would indicate that the shared similarities of lampreys and gnathostomes are convergent or that these characters are absent through loss in the hagfish lineage. These would represent the most extraordinary examples of convergence or degeneracy, respectively, in vertebrate evolutionary history.”

But you are right, Tunicates are highly derived in their own right and not representative of an ancestral chordate common ancestor.

I’m not and expert by any means on microRNA’s, but even if loss happens, wouldn’t that be accounted for in a maximum parsimony analysis? If you look at the microRNA tree they’ve assembled (which I tacked on to the bottom of the post for you) you see many gains and some losses.

Semantically it would still be “between” Tunicates and Cyclostomes, it would just happen after Tunicates split from our last common and before Cyclostomes split. But yeah, I can see where someone might want more precision.

The challenges of writing about systematics for a lay audience. Thanks for you comments.