Last week, Angelo spoke at thew 2024 Our Ocean Conference in Greece about going beyond 30×30 and how we equitably measure ocean success. You can also read his full prepared statement here: What I Meant to Say at Our Ocean Greece 2024

Author: Andrew Thaler

Marine science and conservation. Deep-sea ecology. Population genetics. Underwater robots. Open-source instrumentation. The deep sea is Earth's last great wilderness.Dugongs and Seadragons is the only Dungeons and Dragons Podcast featuring actual marine science professionals playing D&D 5e while talking about marine science, conservation, and all things ocean. It’s been going for a long time, and jumping into the mid-point of an actual play podcast can feel like a daunting task. But we’ve got you … Read More “We Leased the Kraken! Catch up with the ongoing adventures of the Cephalosquad on Dugongs and Seadragons.” »

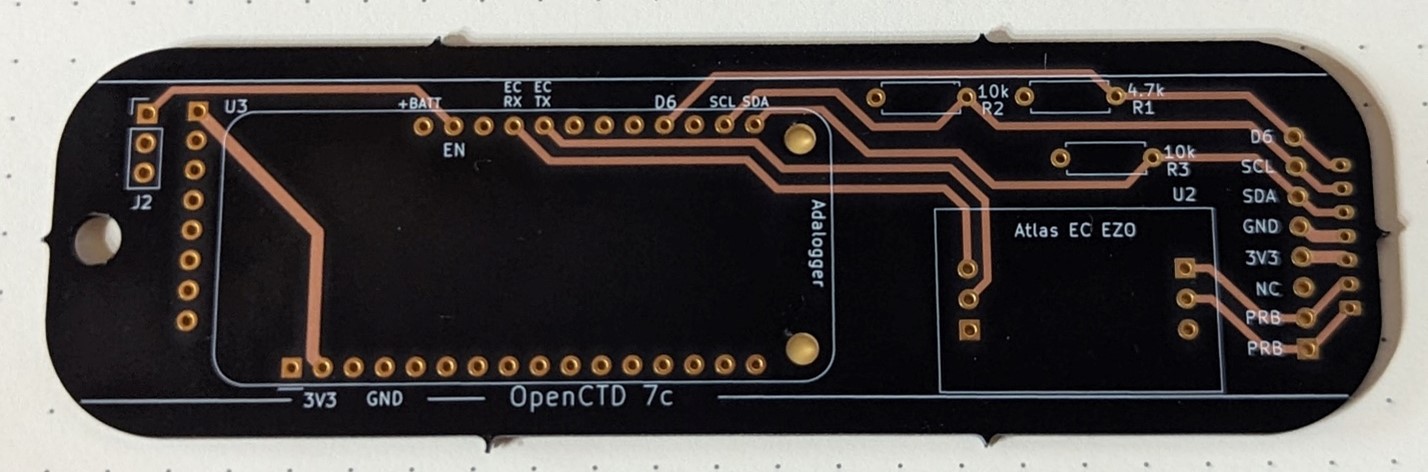

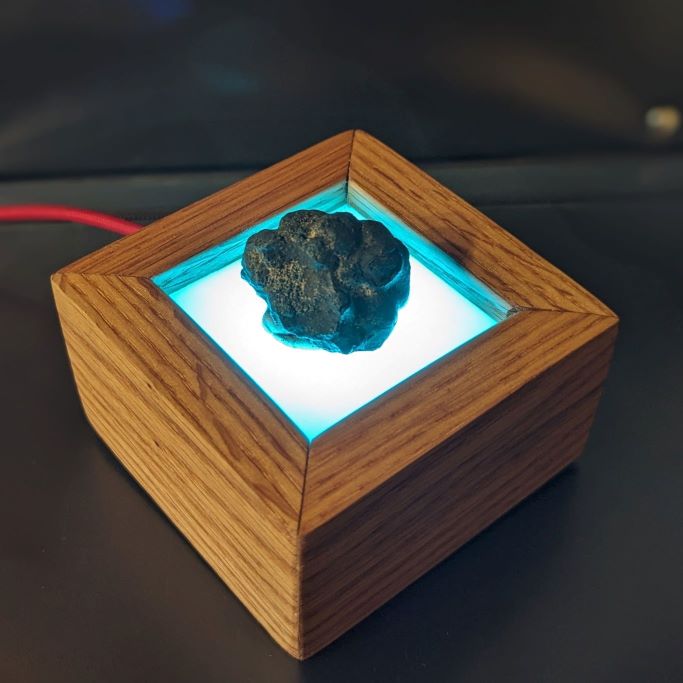

Last month, I wrote a heartwarming little story about how doing a fun weekend hardware project with my daughter led to fixing one of the most annoying non-critical problems with the OpenCTD. After a month of testing, we have fully implemented the new power management system into the next iteration of the OpenCTD. Currently, there … Read More “Charging the OpenCTD is annoying, so we fixed it.” »

After a trio of very widely read articles triggered a traffic surge in February, including David’s critical expert analysis of cross-order hybridization, our visitor count normalized a bit on the old ocean science and conservation blog. A little more than 19,500 people visited Southern Fried Science in March, a roughly 50% increase from January. You … Read More “Space Crabs, Big Boats, and Fake Sharks: What you read on Southern Fried Science in March” »

Early this morning, the cargo ship MV Dali collided with the Francis Scott Key Bridge, causing the bridge to collapse, sending several vehicles and people into the water. Search and rescue is currently underway. Because Twitter is now a clearinghouse for the worst and most disingenuous hacks on the web, there’s of course a rumor … Read More “No, the ship didn’t steer towards the pylon: A brief fact check on the MV Dali collision with Baltimore’s Key Bridge” »

The International Seabed Authority is meeting this month in Jamaica, but it is not the entire International Seabed Authority. Only the Legal and Technical Commission and the Council meet this months. The Legal and Technical Commission is a body of experts that reviews documents and proposals, usually in private as many contain privileged information from … Read More “What I’m watching for at this month’s ISA meeting: The Vibes” »

Cultural Heritage is a bit of a tough concept when working in areas beyond national jurisdiction. By definition, the places being considered for deep-sea mining by the International Seabed Authority exist at least 200 nautical miles from land and human habitation. Even most submerged archeological sites lie on continental shelves within nations’ exclusive economic zones. … Read More “What I’m watching for at this month’s ISA meeting: How to Value Cultural Heritage on the High Seas?” »

The Common Heritage of Mankind. The core principle that underlies all of the negotiations surrounding deep-sea mining beyond national borders is that these resources don’t belong to any one person, organization, or nation, but to humankind as a whole, to be exploited (or not) for the benefit of the world as a whole. With the … Read More “What I’m watching for at this month’s ISA meeting: untangling the financial regime” »

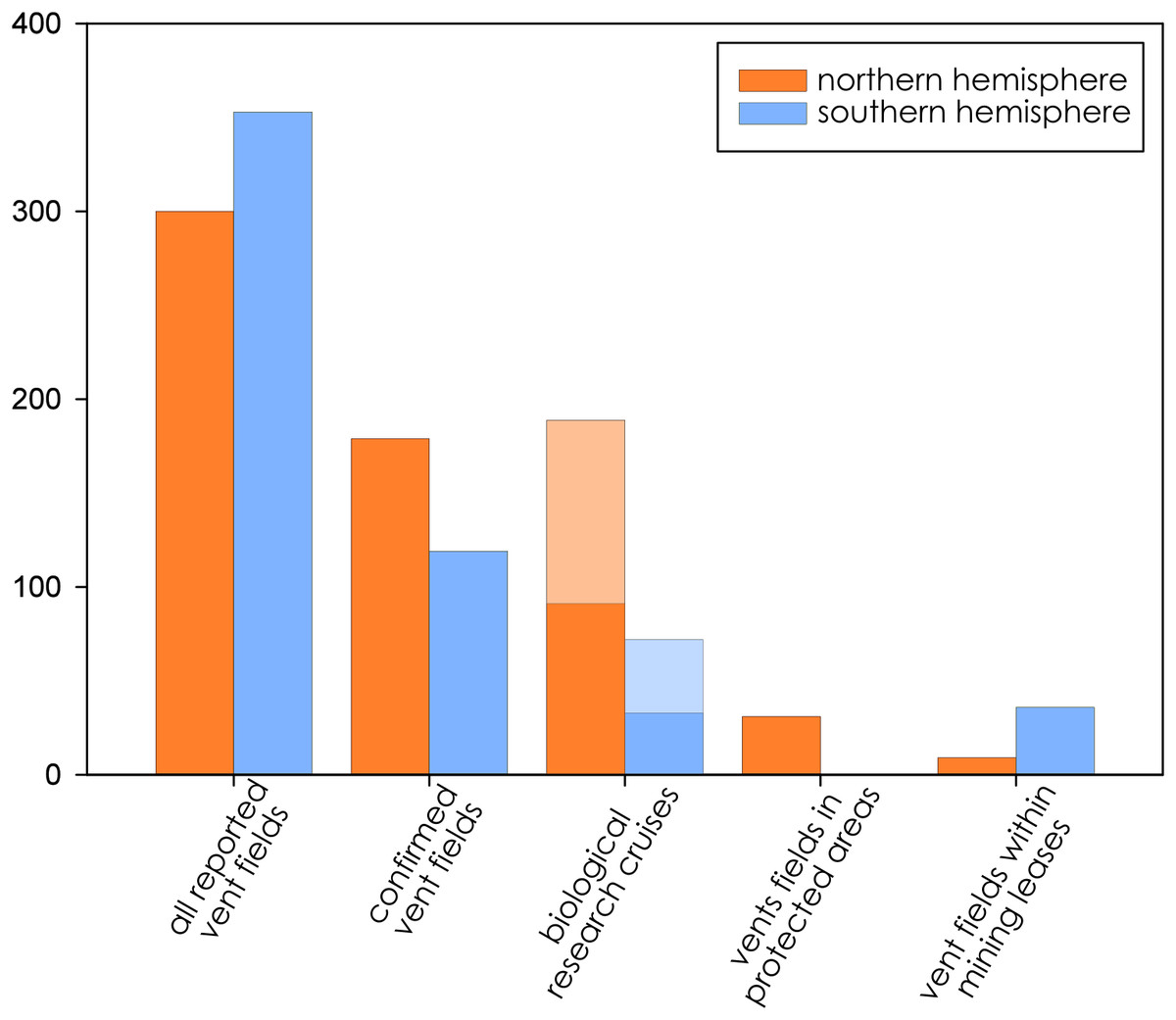

One curious contradiction in the International Seabed Authority is that some of the member states that are currently most vocal about enforcing a strong moratorium (if not outright ban) on deep-sea mining also currently hold ISA exploration leases. The UK and France, as well as Germany and Brazil, have all made statements in support of … Read More “What I’m watching for at this month’s ISA meeting: How are pro-moratorium member states dealing with their own mining leases?” »

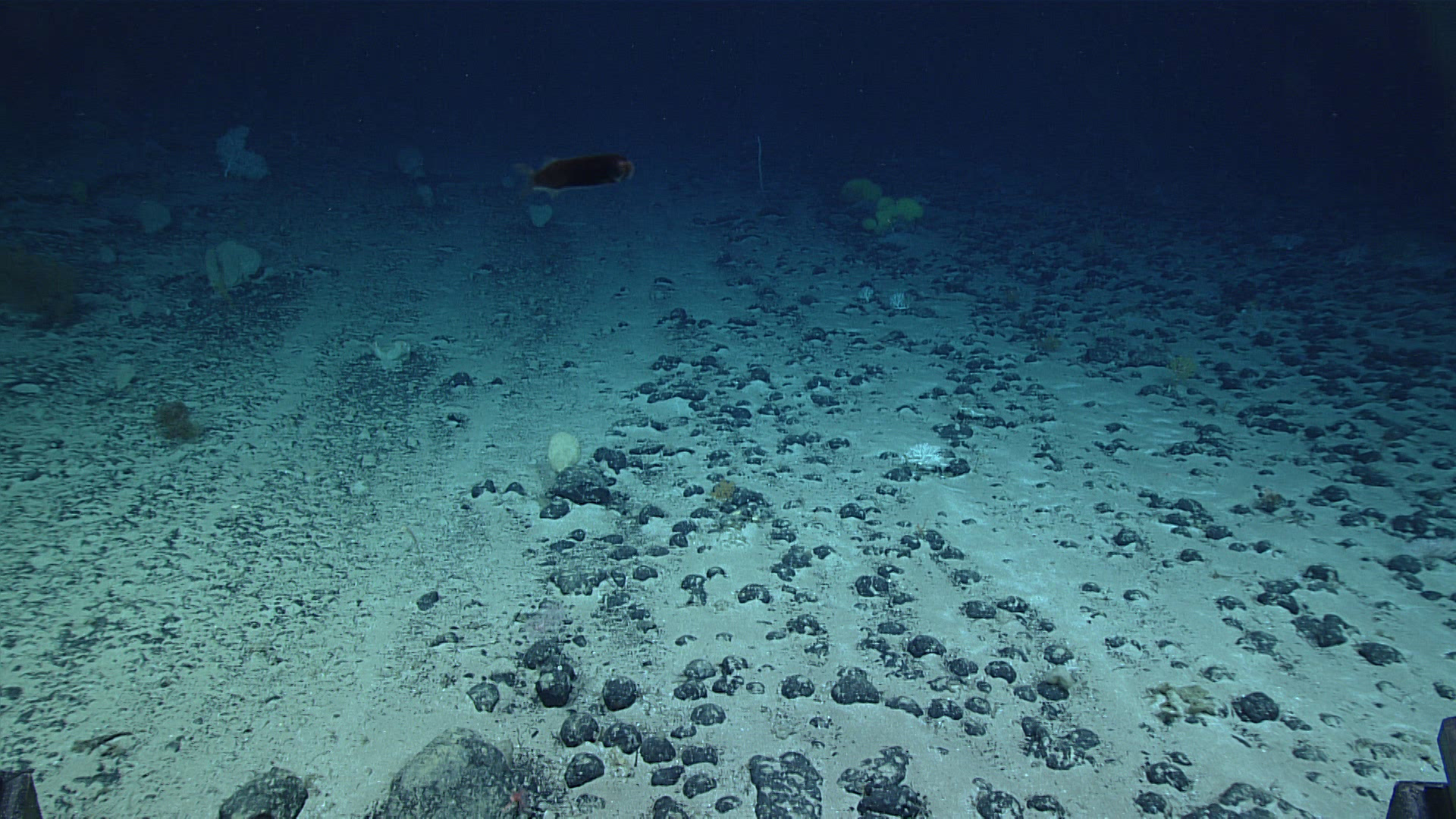

In November and December of 2023, Greenpeace activists boarded a deep-sea mining vessel conducting exploratory research in the Clarion Clipperton Fracture Zone. The executive summary is that the ISA issued interim measure pursuant to Regulation 33 of the Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Polymetallic Nodules in an attempt to compel Greenpeace to halt its … Read More “What I’m watching for at this month’s ISA meeting: How the Council responds to the NORI-D Incident” »