Foghorn (A Call to Action!)

- With ice melting in Canada’s Northwest Passage, the area will soon be a new route for international shipping. Follow Life Under the Ice on OpenExplorer!

Flotsam (what we’re obsessed with right now)

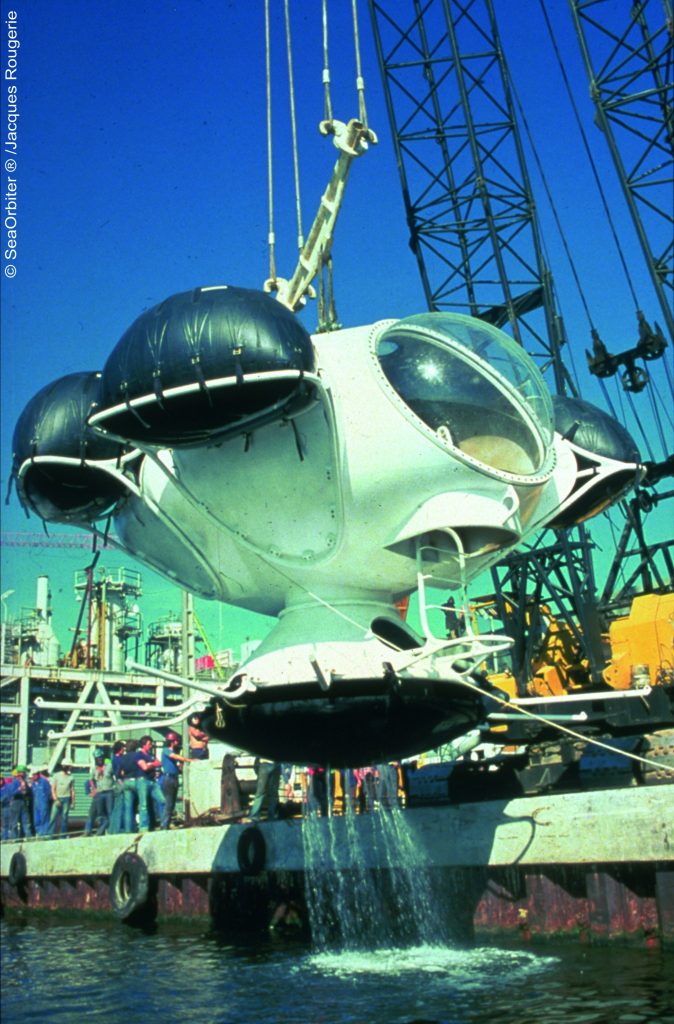

- Legendary submarine pilot Erika Bergman is exploring Belize’s Blue Hole using state-of-the-art SONAR scanning tools and ROVs. A couple floppy-haired dudes are going too.

- DSV Alvin made its 5000th dive. Way to go, little submarine!

- A boon to ocean conservation? Certain fungi can degrade marine plastics.

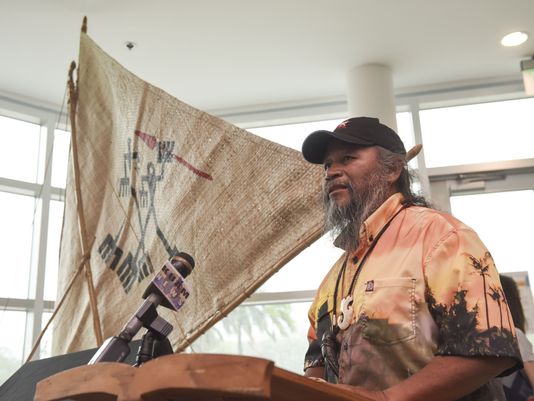

- I missed this over the summer, but Nash was an incredible guide and touring ancient Chamorro caves with him was the highlight of my time in Guam. He will be missed by many: Traditional seafarer Ignacio ‘Nash’ Camacho dies.

Newsweek, in is new and impressive digital format, released a series of articles this week on deep-sea exploration, the challenges of human occupied and remotely-operated vehicles, and the decline in funding for ocean science, particularly in the deep sea. The main article,

Newsweek, in is new and impressive digital format, released a series of articles this week on deep-sea exploration, the challenges of human occupied and remotely-operated vehicles, and the decline in funding for ocean science, particularly in the deep sea. The main article,