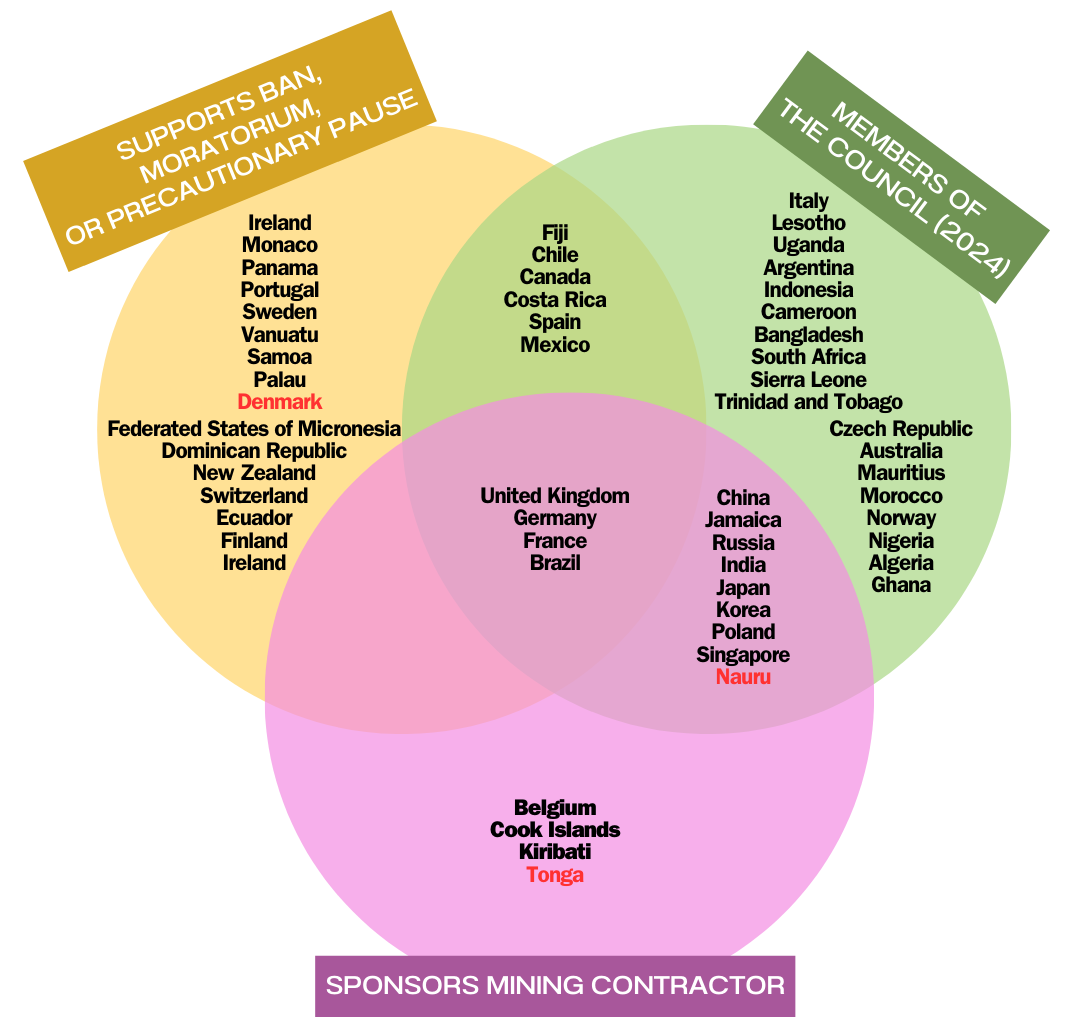

One curious contradiction in the International Seabed Authority is that some of the member states that are currently most vocal about enforcing a strong moratorium (if not outright ban) on deep-sea mining also currently hold ISA exploration leases. The UK and France, as well as Germany and Brazil, have all made statements in support of … Read More “What I’m watching for at this month’s ISA meeting: How are pro-moratorium member states dealing with their own mining leases?” »

Tag: deep-sea mining

In November and December of 2023, Greenpeace activists boarded a deep-sea mining vessel conducting exploratory research in the Clarion Clipperton Fracture Zone. The executive summary is that the ISA issued interim measure pursuant to Regulation 33 of the Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Polymetallic Nodules in an attempt to compel Greenpeace to halt its … Read More “What I’m watching for at this month’s ISA meeting: How the Council responds to the NORI-D Incident” »

Earlier this week, Congresswoman Miller of West Virginia introduced the Responsible Use of Seafloor Resources Act of 2024 bill into Congress. This bill is among the few significant pieces of new national legislation promoting deep-sea mining to be introduced in the modern era. The text is available here: A Bill to support international governance of … Read More “New Deep-sea Mining Bill Introduced in Congress” »

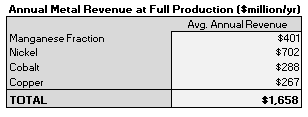

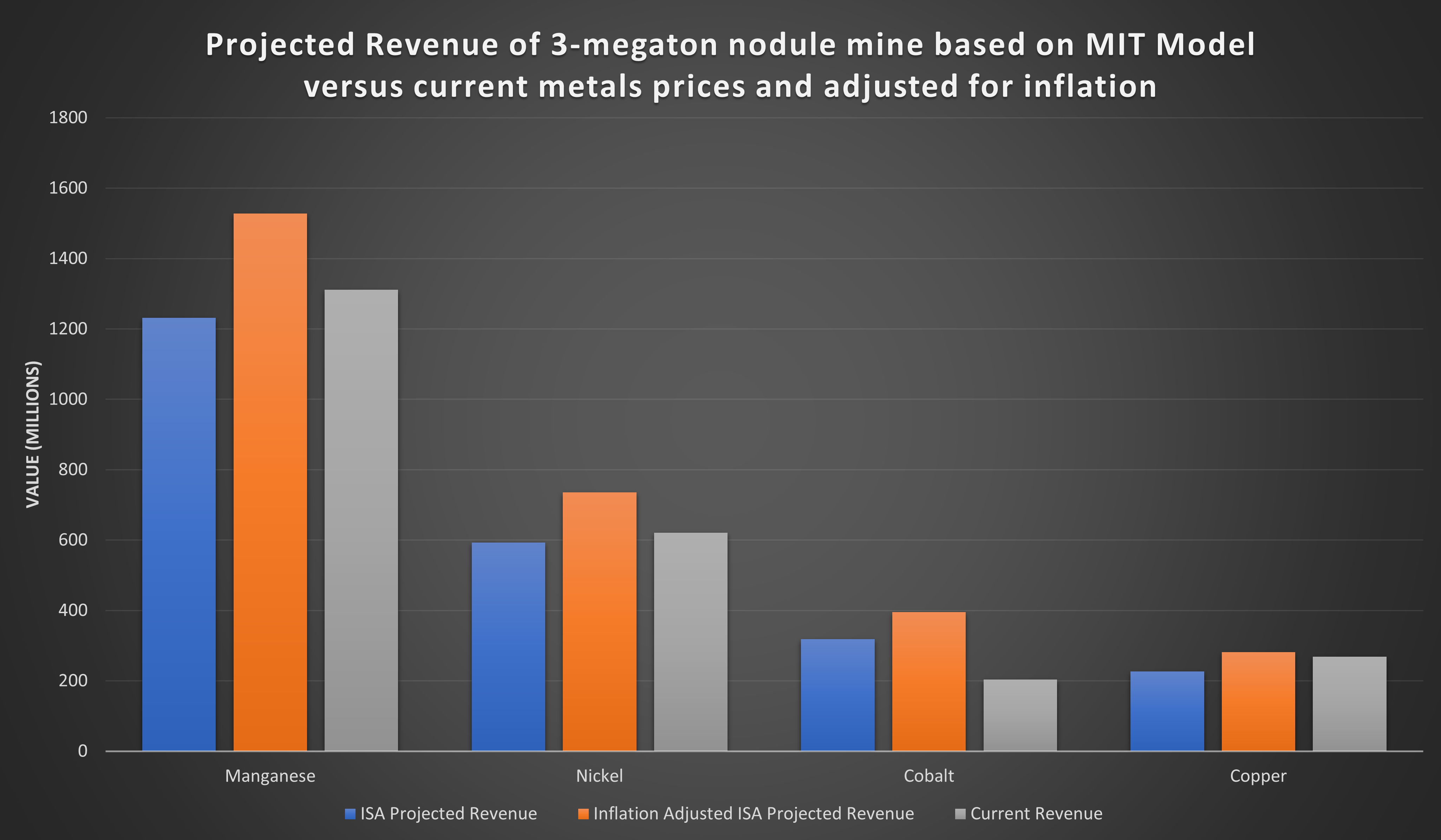

On Friday, I posted about the financial model used to project the potential profits from a hypothetical polymetallic nodule mining model in the Clarion Clipperton Zone. This model, originally commissioned in 2018 and updated in 2021/22, had some puzzling prices for manganese in particular. This model is extremely important. Beginning late this month, member states … Read More “Updated financial model for deep-sea mining makes more sense, fewer dollars” »

Note: please see the update to this post – Updated financial model for deep-sea mining makes more sense, fewer dollars This month, once again, the delegations from 169 countries will gather in Kingston, Jamaica to continue the negotiations on the Deep-sea Mining Code. At this point, I’ve written extensively about the potential environmental impacts of … Read More “Something is bothering me about the Economics of Deep-sea Mining” »

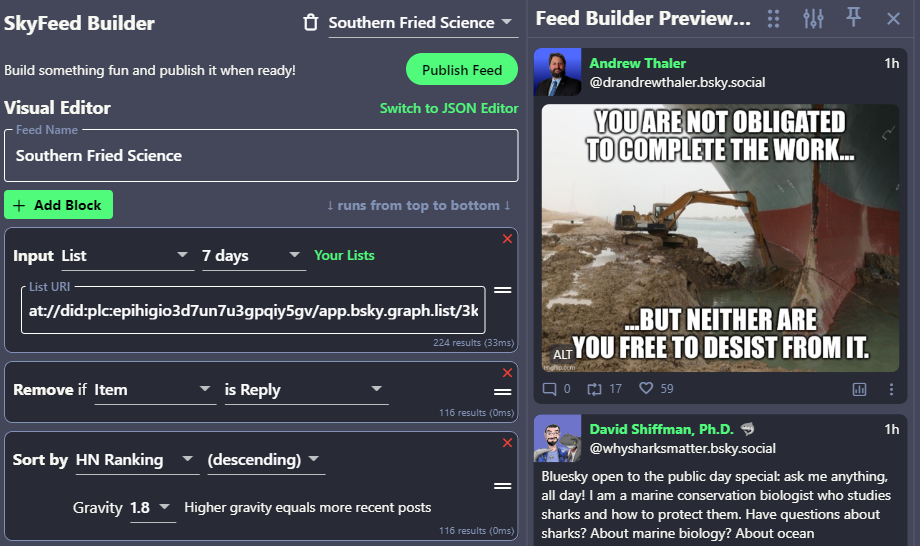

So, you’ve made it! The remnants of science twitter have at last begun to coalesce around a new microblogging platformed owned by questionable individuals with inadequate content moderation that groans under the weight of a massive surge in new users. Welcome to Bluesky. Honestly, it’s pretty great, in the way that Twitter circa 2012 was … Read More “A quick and dirty guide to making custom feeds on Bluesky” »

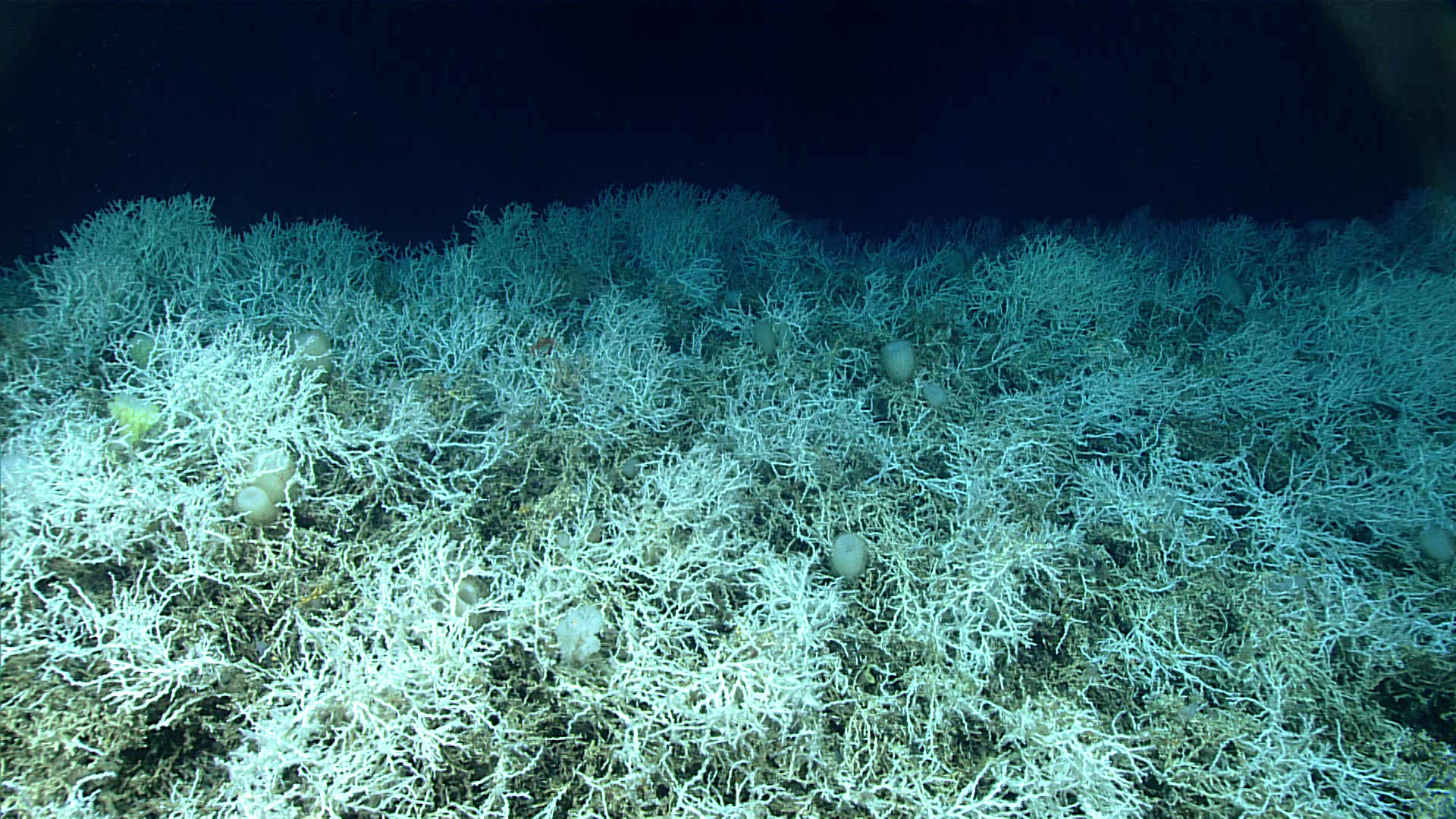

In a region once thought to be so ecologically uninteresting that it was viewed as a useful testbed for deep-sea mining equipment, NOAA researchers have detected what could be the world’s largest cold water coral reef. “For years we thought much of the Blake Plateau was sparsely inhabited, soft sediment, but after more than 10 … Read More “The world’s largest cold water coral reef lies beside the first experimental deep-sea mining test site” »

2023 was a year of endings. I closed several projects and spent a lot of time, behind the scenes, laying the foundation for project I hope will have an impact in 2024. I don’t really think of myself as a science communications person anymore. We are activists, working to achieve specific science-informed policy outcomes. We … Read More “Taking Initiative: My 2023 year in environmental education, outreach, and activism” »

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that deep ocean exploration is an expensive endeavor. Vessels, instrumentation, deep-submergence vehicles, and analytical tools are costly to run and the specialized training needed to maintain that equipment is often a career in itself. Deep-sea research cruises are among the most logistically complex peacetime operations in human history. When access to … Read More “Deep Ocean Exploration needs to move beyond Imported Magic” »

This morning, the Norwegian parliament approved a bill that moves the country one step closer to commercial deep-sea mining in Norway’s waters. This bill opens up nearly 300,000 square kilometers for mining companies to to explore for lithium, scandium, cobalt, and other critical minerals. Importantly, this does not mean that Norway is about to strip … Read More “Norway moves one step closer to deep-sea mining” »