Foghorn (A Call to Action!)

- With ice melting in Canada’s Northwest Passage, the area will soon be a new route for international shipping. Follow Life Under the Ice on OpenExplorer!

Flotsam (what we’re obsessed with right now)

- Legendary submarine pilot Erika Bergman is exploring Belize’s Blue Hole using state-of-the-art SONAR scanning tools and ROVs. A couple floppy-haired dudes are going too.

- DSV Alvin made its 5000th dive. Way to go, little submarine!

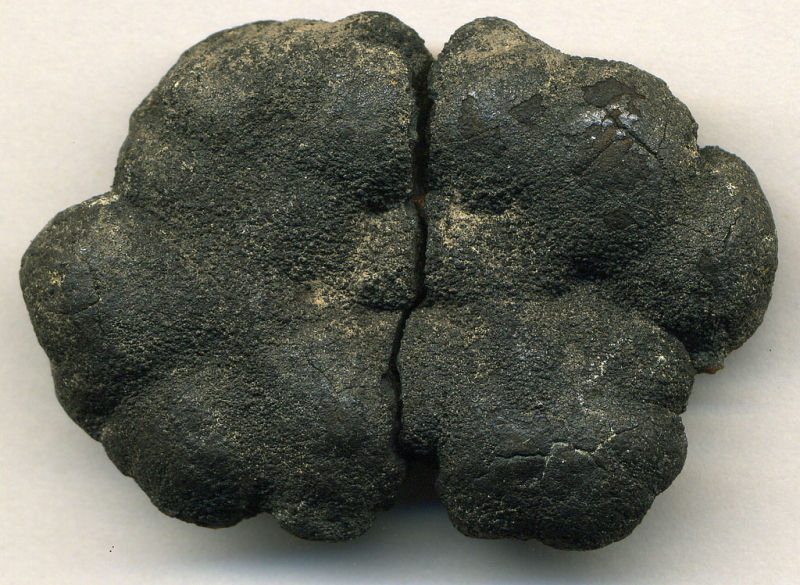

- A boon to ocean conservation? Certain fungi can degrade marine plastics.

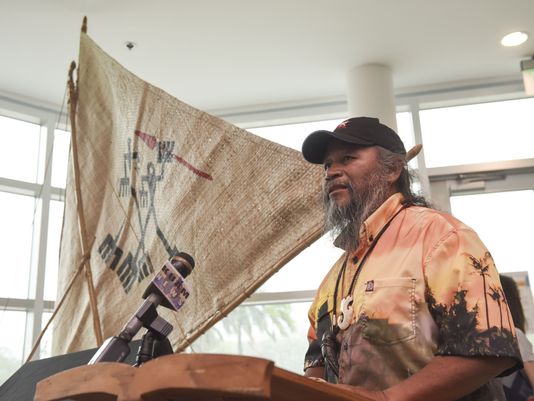

- I missed this over the summer, but Nash was an incredible guide and touring ancient Chamorro caves with him was the highlight of my time in Guam. He will be missed by many: Traditional seafarer Ignacio ‘Nash’ Camacho dies.