Foghorn (A Call to Action!)

In every issue of the Monday Morning Salvage, we try to highlight 2 to 5 papers from the scientific literature. In doing so, we attempt to provide a broad and diverse cross-section of the diversity of people conducting scientific research. However, our priority is in highlighting papers of particular interest to ocean science, and occasionally that means that we end up recommending papers that are exclusively authored by men. A new paper by Salerno and friends highlights the extreme extent to which papers led by men excludes women co-authors.

To do our small part to push back against this phenomenon, we are adopting a new style guide for paper citations. Conventionally, at Southern Fried Science, we use the colloquial “and friends” instead of “et al.” to make paper citations more approachable and less jargon-y. Going forward, in cases where a paper contains only male co-authors, we will instead replace “et al.” with “and some other dudes“.

Flotsam (what we’re obsessed with right now)

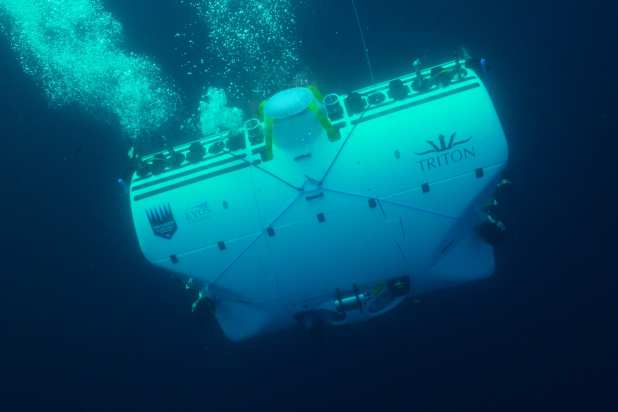

- It is the hero we deserve. Boaty McBoatface Just Helped Solve a Deep-Sea Mystery.

- Shark populations in NC coastal waters are down, despite uninformed opinions based on absolutely nothing.

- It may be formed from rock and plastic, but ‘plasticrust’ is by far the most Metal name they could have come up with. A Strange New Blend of Rock and Plastic Is Forming on a Portuguese Island.