2017 was… yeah. Of all the years I’ve lived through, 2017 was definitely one of them. Anyway, some interesting things happened in the world of shark research. Here, in no particular order, are 17 amazing and important things that scientists discovered about sharks and rays over the last year.

1 Sharks can switch between sexual and asexual reproduction. We’ve known that several shark species can reproduce asexually for over a decade now, but this year, Dudgeon and friends showed an individual shark switching between sexual and asexual reproduction for the first time!

Noteworthy media coverage: CNN, National Geographic, Gizmodo

2 Sharks can expel foreign objects right through their body wall. This study by Kessel and friends showed that over the course of months, an individual shark expelled a small metal object it had ingested right through the side of its body wall, and then healed completely .

Noteworthy media coverage: Earth Touch News, Discover Magazine.

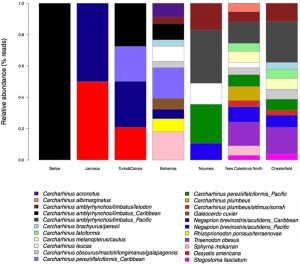

3 Tiger sharks eat penguins and porcupines. Tiger sharks have a well-deserved reputation as being the “trash cans of the sea,” and have been found with all kinds of bonkers stuff inside their stomachs. This year, Dicken and friends published the results of a stomach content analysis study of tiger sharks in South Africa. Tiger sharks in South Africa apparently eat dolphins, small antelope, penguins, and porcupines. They also found garbage including junk food wrappers, cigarettes, and condoms in there.

Noteworthy media coverage: Earth Touch News.

4 Healthy shark populations can be incredibly valuable for local economies by attracting SCUBA divers. While this phenomenon isn’t a new discovery, Haas and friends did an amazing job of thoroughly documenting the benefits of shark wildlife tourism to the economy of the Bahamas. Their conclusions: while shark wildlife tourism is worth an astounding $100 million a year to the Bahamas, many of the economic benefits go to foreign live-aboard vessels who don’t directly help the local economy.

Noteworthy media coverage: The Guardian, the Washington Post. Also I wrote about it for Hakai.

5 Shark diversity can be tracked just from DNA they leave in the environment. While environmental DNA has been applied to marine fishes before, this study by Bakker and friends shows how incredibly this method can be for studying hard-to-find shark species.

Noteworthy media coverage: Yahoo News. (Look for a guest post by Judith Bakker here on SFS in the new year)

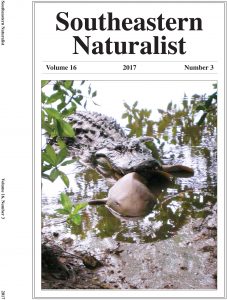

6 Sharks eat alligators, and are eaten by alligators. This paper by Nifong and friends was the most-covered shark research news story of 2017. It describes what’s called “intraguild predation,” when two (or more) predators species that are at approximately the same level in the food chain eat each other, between alligators and four species of sharks and rays.

Noteworthy media coverage: National Geographic, USA Today, Newsweek, the Washington Post, the Guardian, just about everywhere else.

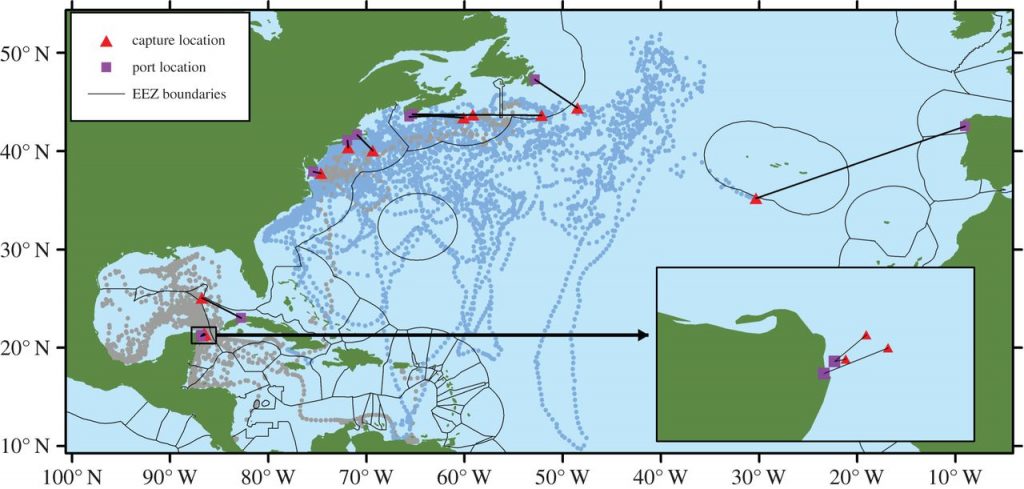

7 More mako sharks are being killed than we thought. By studying patterns of satellite-tagged mako sharks that were caught by fishermen (side note: this is actually not that uncommon), Byrne and friends determined that fishing mortality for mako sharks is higher than we thought. This paper contributed to attempted conservation measures at ICCAT this year.

Noteworthy media coverage: Popular Science, MongaBay.

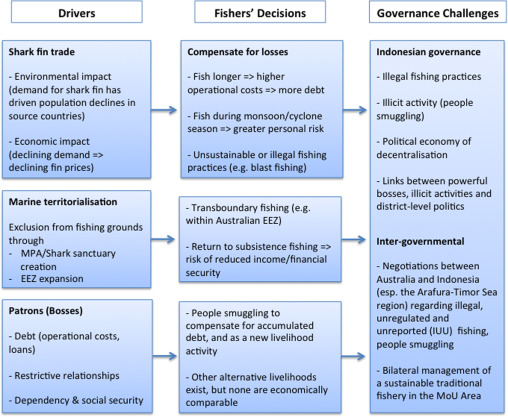

8 If you ban shark fishing without providing an alternative livelihood, bad things can happen. This sobering study by Jaiteh and friends looked at what happened to former shark fishermen in Indonesia. When shark fishing was no longer an option, these fishermen turned to environmentally-devastating dynamite fishing and human trafficking. Conservation is complicated, and you can’t ignore the human side.

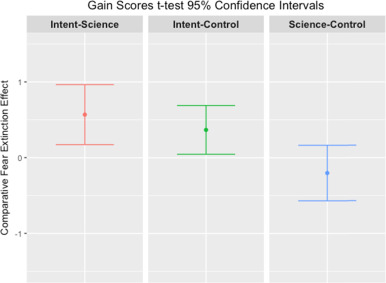

9 Seeing sharks in an aquarium can measurably reduce fear and increase understanding of sharks. Christopher Neff and Thomas Wynter found strong evidence in support of what informal educators have long claimed.

Noteworthy media coverage: Sydney Morning Herald.

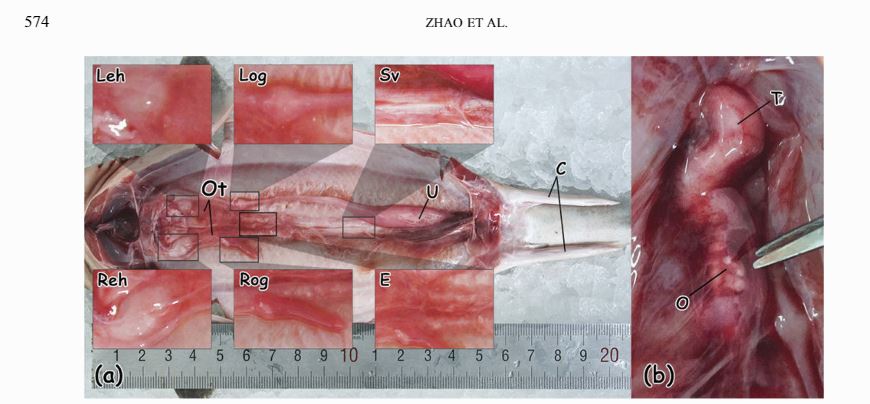

10 Spadenose sharks can have both boy bits and girl bits. Zhao and friends documented the first-ever case of an intersex spadenose sharks, further complicating the already-confusing story of where baby sharks come from.

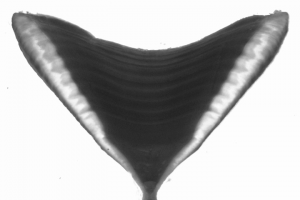

11 Many sharks and rays can be much older than we thought. Al Harry’s work (read his guest post here) identified a possible bias in one of the most common methods we have for estimating the age of shark and ray species, which has important implications for management.

Noteworthy media coverage: National Geographic, Nature, International Business Times.

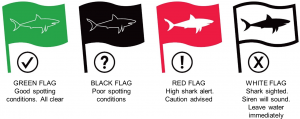

12 Simple ways to protect people from sharks at the beach work just fine. While there are frequently calls for either high-tech solutions (e.g., a network of drones) or lethal solutions (e.g., culls) to protect bathers from sharks, a team in South Africa has shown that in some situations, simple (and non-lethal) solutions work just fine. The Shark Spotters program is a network of trained volunteers that look for sharks from shore, and alert people when they’re nearby. A new report by Engelbrecht and friends found that this simple solution significantly reduced the overlap of swimmers and sharks, saving lives without requiring anyone to kill threatened species of sharks.

Noteworthy media coverage: All Africa News.

13 Whale shark population trends and migration patterns can be tracked using citizen science! Using a global network of citizen scientist SCUBA divers over decades, Norman and friends identified 6,000 individual whale sharks, and were able to track their migration patterns!

Noteworthy media coverage: National Geographic, Newsweek, the New York Times.

14 Researchers tracked the causes and rates of spontaneous abortion among captured sharks and rays. When sharks are caught by fishermen, they often give birth prematurely, giving their young at least a chance at survival. Adams and friends systematically reviewed the literature on this important and understudied topic, and also searched for angler’s social media posts to determine if it happens more than we thought.

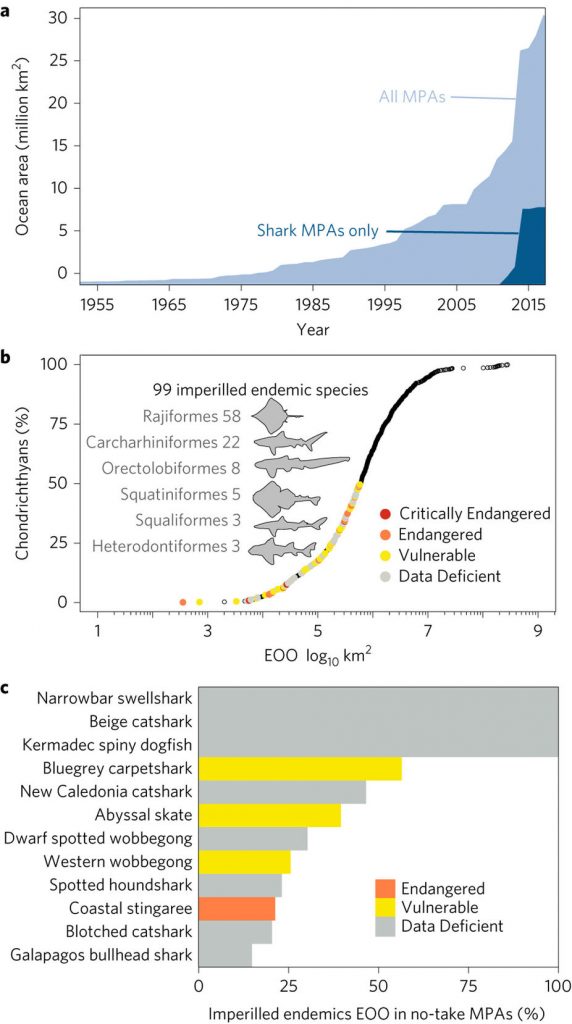

15 The current network of marine protected areas doesn’t cover the range of threatened sharks and rays. Through a global-scale GIS analysis comparing where the most threatened species of sharks and rays live and where marine protected areas are currently established, Lindsay Davidson and Nick Dulvy* found that MPAs aren’t doing enough to protect these species. They also found that more than half of all threatened species live the waters of just a dozen countries (four of which are heavy shark fishing nations that don’t have any kind of management or conservation plan in place,) and that a 3% expansion of the total MPA area could protect half the habitat of nearly 100 threatened species.

Noteworthy media coverage: Radio Canada

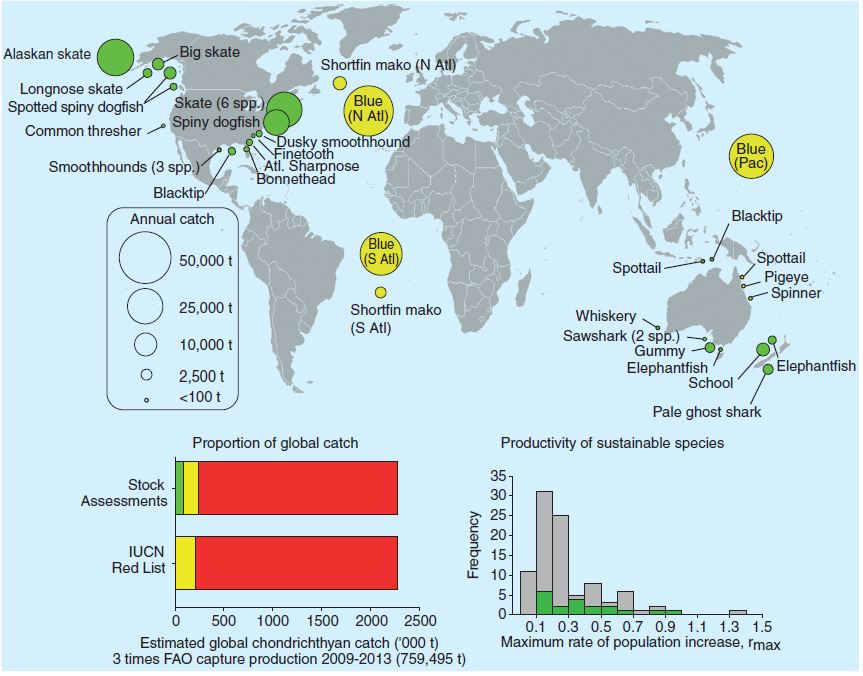

16 There are places where sharks are being fished sustainably, providing a template for other nations to follow. IUCN Shark Specialist Group co-chairs Colin Simpfendorfer and Nick Dulvy* analyzed stock assessments and management plans for the world’s shark fisheries and determined that approximately 9% of global shark and ray landings come from biologically sustainable, well-managed fisheries. While this means that most shark and ray fisheries are not currently sustainably managed, it also means that shark and ray fisheries can be sustainably managed, and that there are successful models out there for others to follow.

Noteworthy media coverage: Scientific American (quotes me), CBC news, Christian Science Monitor.

17 Recreational shark anglers in Florida brag about breaking shark fishing laws online. I hope you’ll forgive me for including some of my own work on this list. By analyzing over 1,000 posts made to an online discussion forum used by recreational shark anglers, we identified hundreds of cases of clear unequivocal violations of fishing regulations, along with evidence that many anglers knew that they were breaking the rules. We also found cause for hope, as many anglers expressed evidence of a conservation ethic. Learn more about it from my blog post here.

Noteworthy media coverage: Miami Herald, National Geographic, Nature, the Revelator, On Earth.

*Author’s note. Nick Dulvy is my Postdoc supervisor. FWIW, both of these papers were published before I arrived in his lab.

Are #16 and #7 in conflict with one another?