Just how long should a woodworking joint last?

Towards the middle of 2021, I started writing what could be generously described as a manifesto for environmentally conscientious woodworking. In Furniture as Revolution, I argue that: “In a present defined by levying a tax on future generations through manufactured frailty, making something designed to persist beyond the lifetime of its creator is a radical environmental act. It is a reminder that we can act with foresight, that we are betting on resilience, not surrender. It is a rejection of the conspicuous consumption that has shaped the current era. And it is a promise to the future that we intend to endure.”

So how long can a well crafted woodworking joint last?

As of now, half-a-million years.

One of the problems with unearthing the ancient history of woodworking is that wood degrades. While we have numerous stone structures that may have been cut and hoisted and hauled and shaped and set by wooden tools, and which still bear the maker’s marks from those tools, the tools themselves are long gone. It’s why we don’t know precisely how things like Stonehenge or the Pyramids were shaped and moved even though we know generally how they could have been. We see the legacy of the craft, but not the craft itself.

In my absolute favorite non-ocean research paper of 2023, archaeologists in Zambia excavating a bank of the Kalambo River uncovered, among a treasure trove of prehistoric wooden tools, a pair of logs from a bushwillow tree.

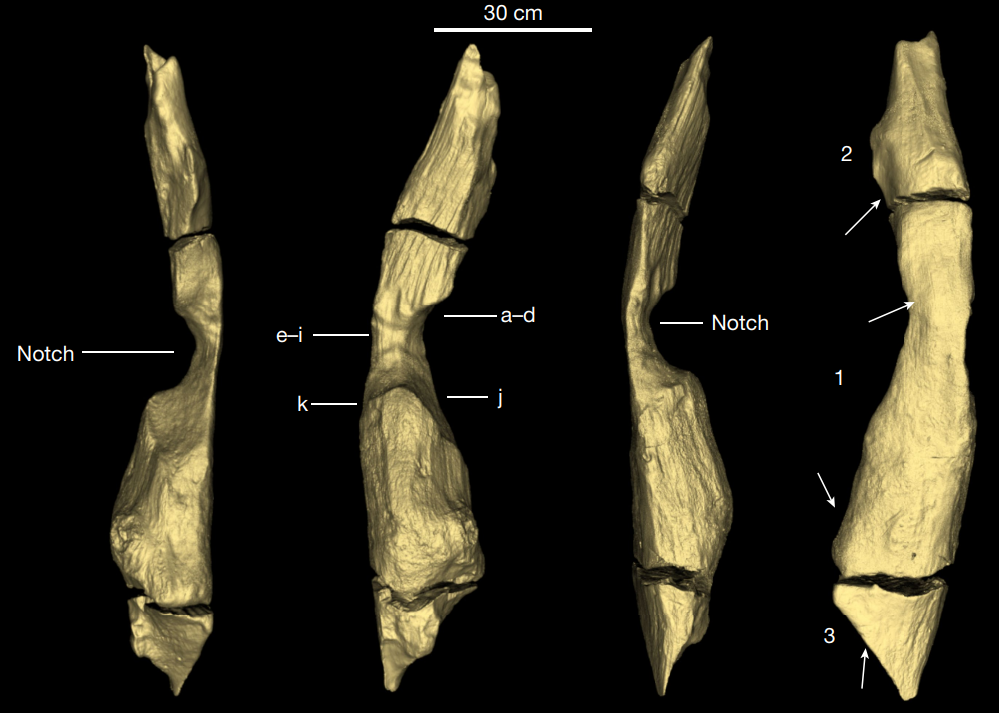

It’s not a particularly complex joint, just two overlapping logs, with a notch cut into one, stacked one on top of the other to create an interlocking structure. Its lack of complexity should make it immediately familiar to just about anyone. If you’ve ever looked at the walls of a log cabin, or stacked Lincoln Logs, or run out a stacked rail fence, you know this joint.

Was it the wall of a free standing structure? The foundation of a platform? A fence to pen in animals or a weir to trap fish? Whatever its use, it was built, with intention, by modifying two pieces of wood and then combining them together with a joint that outlived its makers.

Notched logs weren’t the only thing Barham and their team found. Among the artifacts were a shaped wedge and a digging stick, all of which bore clear signs of human alteration. Except they weren’t humans, at least not modern Homo sapiens, not yet. While there were a few different members of genus Homo wandering across the world at the time, it’s not clear which human ancestor occupied the Kalambo Falls region in the Mid-Pleistocene. The nearest remains to the site are a 300,000-year-old skull from Homo heidelbergensis.

I live in a log cabin. Despite our rural aesthetic, I’d be willing to wager that I live in one of the most technologically advanced houses ever constructed. My home is a cybernetic wonderland of heat pumps and induction stoves, built with sophisticated structural engineering to handle an ever changing climate, and housing a 3D fabrication facility that works in plastic and metal and even wood and a command center connected to an array of smart buoys and ocean sensors deployed around the world.

And yet, our walls are their walls, an unbroken chain of craftsmanship stretching back half-a-million years, shared between species who were almost, but not yet entirely, us.

A good joint is built to last.

Evidence for the Earliest Structural Use of Wood at Least 476,000 Years Ago is available, open-access, in the journal Nature.

This article is part of my series Built to Last: A Reflection on Environmentally Conscientious Woodworking.

- Built to Last: A Reflection on Environmentally Conscientious Woodworking

- Part 1: I turned my woodshop into a personal solar farm.

- Part 2: Getting a handle on workworking chemicals, or sometimes we all need to vent.

- Part 3: Furniture as Revolution.

- Part 4: The best tool for the job is you

- A good joint is built to last: archaeologists uncover evidence for the earliest structural use of wood.

Southern Fried Science is free and ad-free. Southern Fried Science and the OpenCTD project are supported by funding from our Patreon Subscribers. If you value these resources, please consider contributing a few dollars to help keep the servers running and the coffee flowing. We have stickers.

Featured image: Two logs, notched and joined, 500,000 years ago, from Barham et al. 2023.