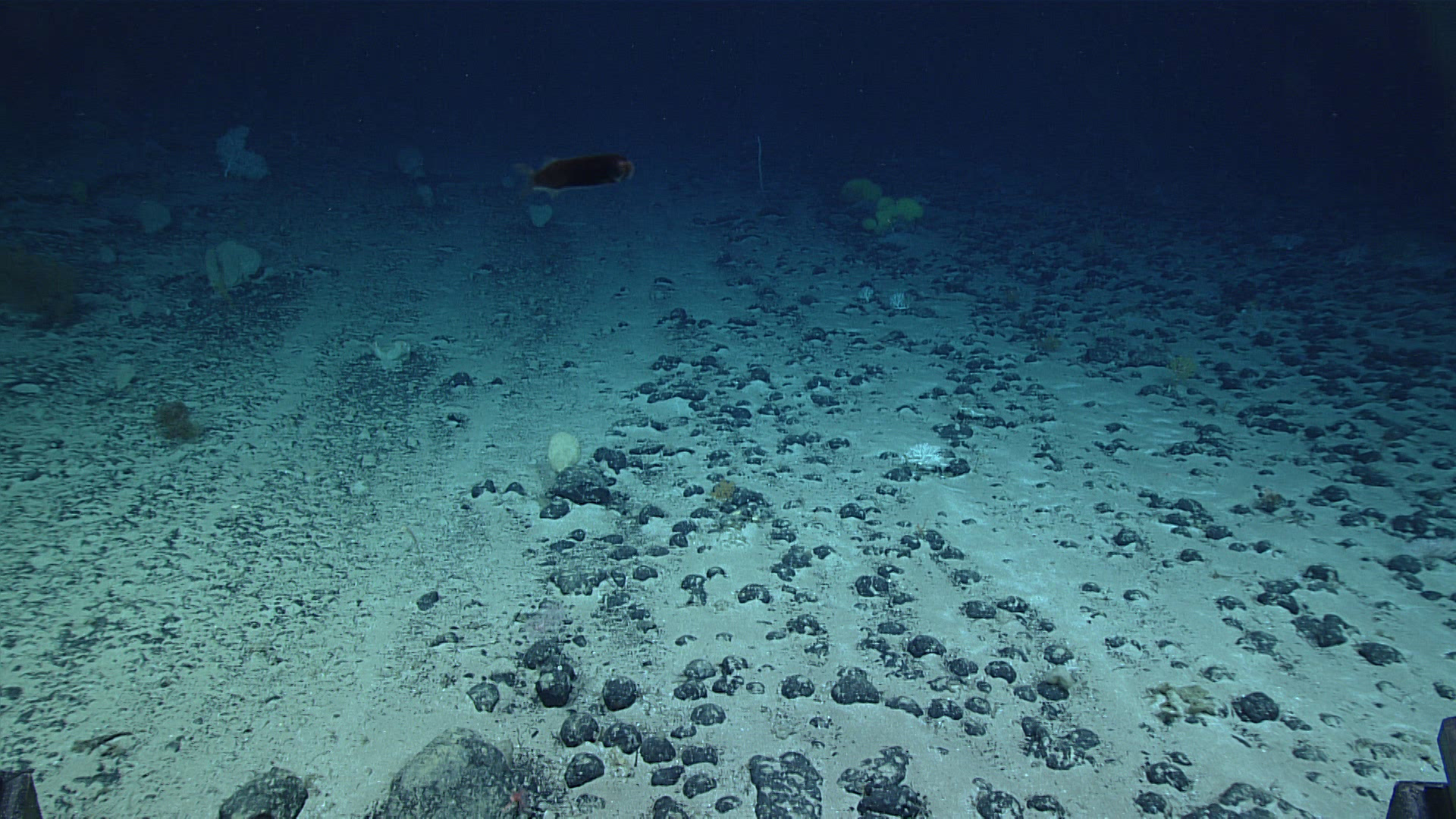

Nodules, a new documentary by Clare Fieseler and Jason Jaacks takes a deep dive into polymetallic nodule mining and two recent discoveries that help reshape our understanding of the seafloor. Fieseler explores the discovery of dark oxygen production in nodule fields and the rediscovery of the world’s first deep-sea mining test site on the Blake Plateau, and asks why some deep ocean discoveries break through into the public consciousness while others languish in scientific obscurity.

I had the privilege of joining Fieseler, Jaacks, and international lawyer Toby Fisher at the premier of Nodules during the 30th Session of the International Seabed Authority for a panel discussion on science, law, and the media. That event marked my return to the ISA after a five year hiatus.

Over the last almost 20 years, I have been a researcher, a consultant, a journalist, an activist, and a technician. I have worked with deep-sea mining companies and worked against deep-sea mining companies. I have advised NGOs, governments, and intergovernmental agencies on science-informed policy. I ran the only trade journal dedicated exclusively to following developments in deep-sea mining. I’ve been outspoken in my criticism of the previous ISA leadership and on the Unitary Mining Code. I teach the only graduate-level course on the environmental impacts of deep-sea mining in the US. It is fair to say that few people in the deep-sea mining world have worn as many different hats as I have.

I annoy my friends from the industry by taking a firm stance that some forms of deep-sea mining–mining at active and inactive hydrothermal vents–should never be allowed to proceed. I annoy my friends in NGOs by being willing to entertain the possibility that some forms of mining–extremely well-regulated and transparent polymetallic nodule mining–might have a future.

My history with deep-sea mining goes back to 2008. After a false start working on deep-sea fungi, I began my PhD researching investigating the environmental impacts of the Solwara I hydrothermal vent mine in Papua New Guinea and developing biodiversity and connectivity baselines to better understand how vents spread across the Western Pacific are tied to each other. I’ve written a lot about this project over the years.

The short version of my Nautilus Minerals story is this: I entered into a research partnership with Nautilus with an open mind and in good faith. Their environmental team had a reasonable argument for why the specifics of this site, in this place, could be resilient to significant disturbance. Throughout the course of my research over 5 years, it became clear to me that there almost certainly was no way to mine Solwara I, or any hydrothermal vent, active or inactive, without causing significant harm to the immediate vent ecosystem as well as knock-on effect to vent ecosystems downstream and across the Western Pacific.

There’s no grand narrative about the evils of industrialization, here. The environmental scientists I worked with at Nautilus were genuinely concerned about harms to the ecosystem. They put together the best possible case for an environmentally conscientious mining project and the fact that I, and most other deep-sea scientists, felt that it fell short is no criticism to them. Nautilus did eventually get a license to mine Solwara I, but it went bankrupt before production could begin, the ship they needed never built. Their mining tools rusting away in Port Moresby.

I haven’t really told that story publicly before, but that’s an important arc of environmental science, where we’re not de facto opposed to all forms of development, but willing to work across industries in good faith, to take our time really understanding the environmental impacts, and to speak frankly and openly about what we’ve discovered. It’s why I continue to frustrate some of my colleagues by not unilaterally condemning all nodule mining projects. It’s also why, when I say that there is no environmentally responsible way to mine a hydrothermal vent, it comes from a place of deep understanding.

I am seeing that same arc play out with my friends and colleagues working in deep-sea nodule mining. As they discover more and more about how weird and wild and wonderful these vast cobble fields are and learn more about the long term implications for mining them, independent researchers who have worked, in good faith, with the nodule mining companies are increasingly coming to the conclusion that we just don’t know enough about deep seafloor to make a responsible decision about how best to mine them. Not yet.

Dark Oxygen is a tantalizing story that needs an awful lot more research before we can understand what’s going on there. We don’t even know the mechanism through which oxygen is produced in a nodule field. Key to the dark oxygen story is that fact that this research was funded by The Metals Company. The discovery was facilitated by deep-sea mining and the researchers involved, with projects dependent on support from the company to persist, are coming out and saying that there’s something important happening on the deep abyssal plain and we should take a step back and figure it out before mining is allowed to begin.

All victories are temporary. All losses are permanent.

The tragic reality of conservation work is that victories are temporary and losses are permanent. Conservation is an ongoing struggle against biodiversity loss, climate change, pollution, and myriad other insults to our planet. And that struggle doesn’t end. There’s no finish line, no moment when we can sit back and declare the work done.

Loss is permanent. Extinction cannot be reversed. A shoreline lost can be replaced, but never restored to its original state. A forest torn down can be regrown as something new, but never returned to its past. A hydrothermal vent mined is a community lost.

The fight to protect Solwara I continues. Solwara I keeps remerging, a zombie project that doesn’t want to die. After the company went bankrupt, its assets were bought by a finance company, backed by some of the company’s original investors. Some of its assets were sold on, most notably its exploration license for Tonga to The Metals Company, some of its assets, including the mining license for Solwara I remain with the holding company.

In 2024, a vessel usually used by The Metals Company to conduct exploration and experimental seabed mining test by the Metals Company appeared in Papua New Guinea waters and began a new round of test mining at Solwara I. The reports of its operation were sketchy, the condition of its mining permits were obscure. The government made no comments. For a moment, it looked like Solwara I was back on the chopping block.

At UNOC, the Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea declared that the country was opposed to seabed mining and would adhere to the conditions of the Pacific Moratorium. For the moment, it appears that Solwara I will not be mined. There are still forces that want to develop Solwara I. The mining license is up for renewal, and there is a case to be made that, without the mining tools and support vessel proposed by Nautilus Minerals, the license is no longer valid.

The hydrothermal vents at Solwara I are among the most biodiverse hydrothermal vents in the world. Losing even some of that biodiversity and genetic novelty could have ripple effects that extend throughout the western Pacific.

For now, Solwara I endures. It is a temporary victory.