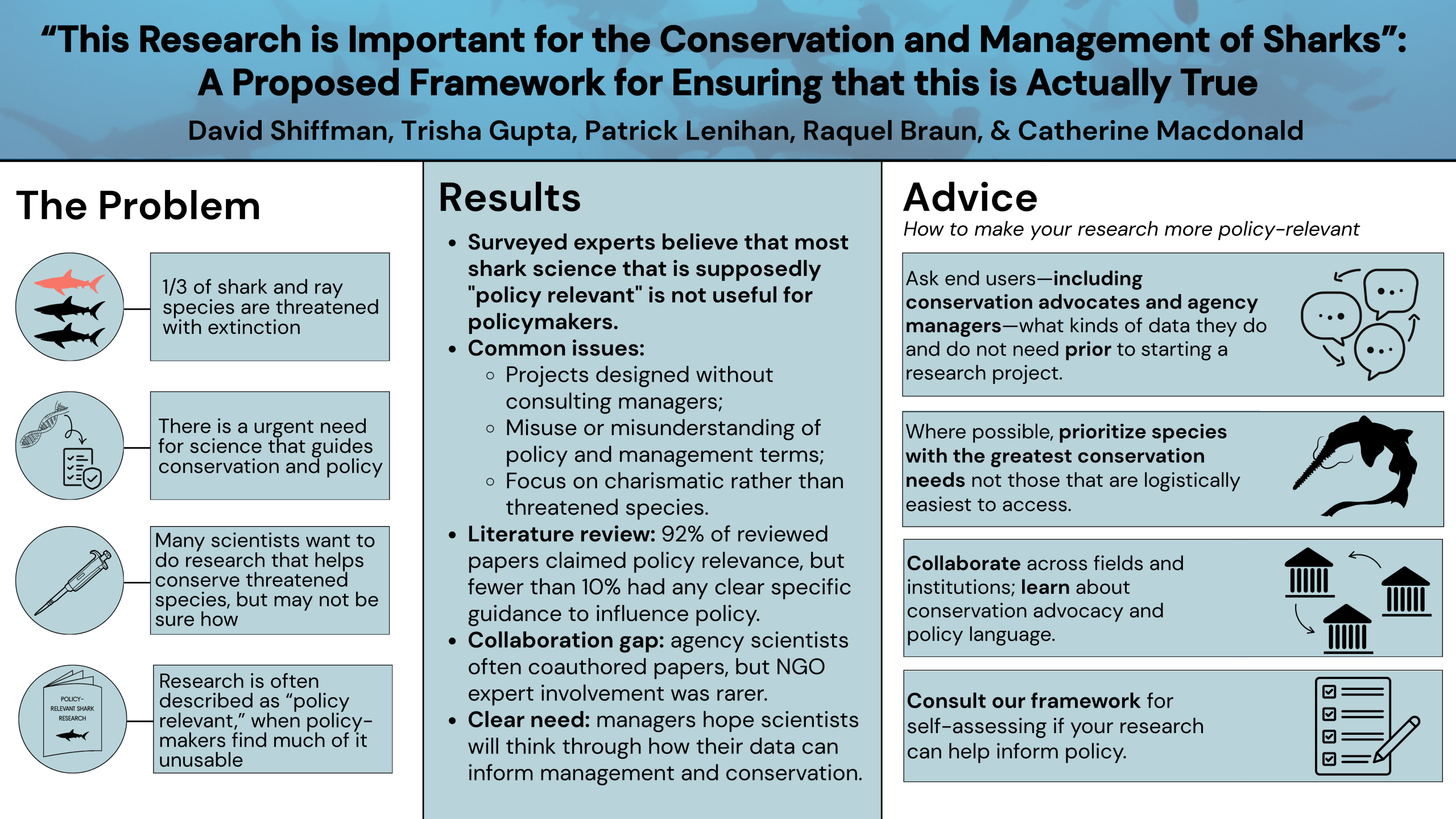

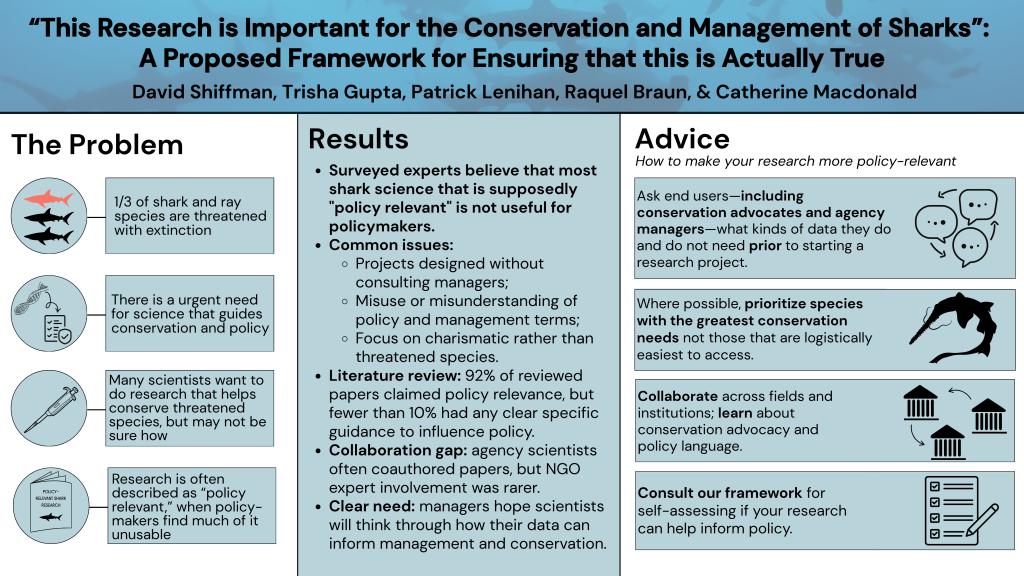

Sharks are some of the most threatened animals on Earth, and accordingly many scientists who study sharks want their research to be useful for conservation. However, most scientific training does not include a detailed explanation of the policymaking process, resulting in lots of shark research being positioned as relevant to conservation and policy when it really is not. The phrase “this research is important for the conservation and management of sharks,” which appears frequently in shark research papers and scientific presentations, has become a point of frustration or even mockery by some natural resource managers and conservation advocates.

Our new paper can help! “This research is important for the conservation and management of sharks: a framework for ensuring that this is actually true” is out now in the interdisciplinary environmental science journal Conservation Science and Practice.

Our team has previously interviewed shark conservation advocates and natural resource managers who implement shark conservation policy. In our new paper, we present those experts’ previously-unpublished thoughts on the state of scientific research intended to be conservation-relevant, and their advice for scientists who want their research to make a real impact in the policy world.

Advice includes “ask natural resource managers what kind of data they need and do not need before you start a research project,” as opposed to assuming that any kind of data will automatically be helpful. Wherever possible, scientists are encouraged to study species with the most pressing conservation needs, as opposed to species that are most charismatic or logistically easy to access. Collaboration, including with government agency employees and environmental advocates, is also encouraged.

We also present a novel framework that can help scientists to assess whether or not their research is likely to be useful for conservation policymaking.

“The most effective conservation policies are based on scientific evidence, but far too few scientists know how to frame their results in ways that policymakers can use,” says lead author Dr. David Shiffman, a marine conservation biologist and ocean conservation policy consultant in Washington, DC. “The advice in this paper can help scientists, conservation advocates, and policymakers to better work together.”

“In the same way that scientists develop hypotheses before beginning a study, they need to consider the applications their work can have for conservation and management as a foundational component of research design,” says senior author Dr. Catherine Macdonald, associate professor at the Rosenstiel School at the University of Miami. “There’s nothing wrong with conducting studies that don’t have direct conservation applications–but where scientists are looking to meaningfully contribute to policy, that goal requires consideration and planning.”

“A lot of shark conservation research doesn’t actually help save sharks,” says coauthor Dr. Trisha Gupta, a conservation scientist at the Zoological Society of London. “Our study shows that small changes in how we design, conduct and communicate research can dramatically improve its usefulness for real-world shark conservation.”

Study authors Dr. David Shiffman, Dr. Catherine Macdonald, and Dr. Trisha Gupta are available for an interview. Please contact Dr. Shiffman (WhySharksMatter @ gmail.com, subject line “MEDIA REQUEST”) with any inquiries.