Transcript below.

Tag: Gulf of Mexico

Foghorn (A Call to Action!)

- We’re live from the 25th General Assembly of the International Seabed Authority. Watch here!

- Update your indices. This marine worm is called the Sand Striker.

[source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/26598370@N00/5205585822]

Flotsam (what we’re obsessed with right now)

- This is very much not normal. An Extremely Rare February Typhoon Is Approaching Guam.

- US Coast Guard Officer Suspected Of Terror Plot Faces Charges.

Foghorn (A Call to Action!)

Flotsam (what we’re obsessed with right now)

- So many mesmerizing videos from Deep Sea News! Experience the Life of the Deep Gulf of Mexico in 20 Videos.

- This is a staggeringly beautiful image: One Great Shot: The Guillemot and the Iceberg.

- Did you lose a flash drive? NIWA might have it. They were defrosting leopard seal poo…you won’t believe what happened next!

Foghorn (A Call to Action!)

- Melissa Márquez is fundraising to participate in a women-in-science leadership retreat that culminates in a 2.5 week trip to Antarctica. Help her out! Or back her Patreon!

- The scandal-plagued, utterly ineffective, Scott Pruitt is out, just days after an American patriot told him exactly how she felt about him in a restaurant. Good.

Flotsam (what we’re obsessed with right now)

- Investing in indigenous communities is most efficient way to protect forests, report finds. This should surprise no one but it often does.

- Explore the deep waters around Kiribati with OpenExplorer!

The Levee (A featured project that emerged from Oceandotcomm)

- Virtual Reality Preserves Disappearing Land: Coastal communities are capturing their cultures and landscapes in virtual reality before sea level rise steals them for good.

- Where Did the Oil Go In the Gulf of Mexico? a storymap.

Foghorn (A Call to Action!)

- Yale study: Newspaper op-eds change minds and The Long-lasting Effects of Newspaper Op-Eds on Public Opinion. Scientists and conservationists, this May, make an effort to publish a Letter to the Editor or OpEd in your local paper. If you’ve done so, please leave a link to it in the comments.

- How to save the high seas: As the United Nations prepares a historic treaty to protect the oceans, scientists highlight what’s needed for success.

Flotsam (what we’re obsessed with right now)

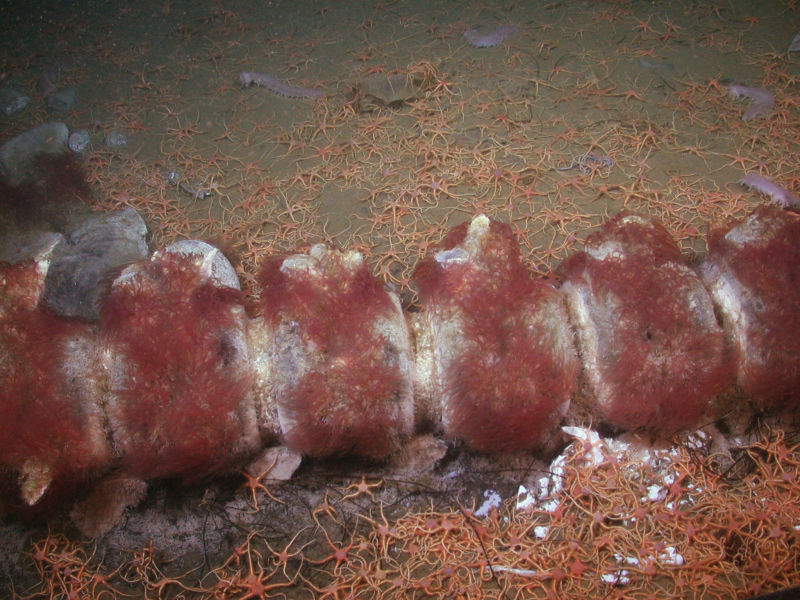

- No commentary needed: Eyeless, Mouthless, Bone-Eating Worm Named After Jabba the Hutt.

Photo: 2006 MBARI

- Every ocean, every dive, every time, trash: Plastic Bag Found at the Bottom of World’s Deepest Ocean Trench.

This blog post and photo slideshow was created during OCEANDOTCOMM, an ocean science communication event, and supported by the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium (LUMCON) The theme of OCEANDOTCOMM was Coastal Optimism. Photos were contributed by our lead photographer, Rafeed Hussain/Ocean Conservancy, with additions from other OCEANDOTCOMM attendees, including Melissa Miller, Samantha Oester, Susan Von Thun, Solomon David, Rebecca Helm, and Alexander Havens.

This blog post and photo slideshow was created during OCEANDOTCOMM, an ocean science communication event, and supported by the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium (LUMCON) The theme of OCEANDOTCOMM was Coastal Optimism. Photos were contributed by our lead photographer, Rafeed Hussain/Ocean Conservancy, with additions from other OCEANDOTCOMM attendees, including Melissa Miller, Samantha Oester, Susan Von Thun, Solomon David, Rebecca Helm, and Alexander Havens.

In many ways, South Louisiana is seafood- a trip here isn’t complete without eating some gumbo, oysters, or crawfish. Only one state (Alaska) lands more seafood than Louisiana’s 1.2 billion pounds a year (as of 2016). As of 2008, one in 70 jobs in the whole state is tied to fishing or related industries. According to the Louisiana Seafood Marketing and Promotion Board, “when you choose Louisiana seafood, you’re ensuring that your purchase benefits an American community and a way of life.”

When we visited Terrebonne Parish, home to nearly 20 percent of all commercial fishing license holders in Louisiana, we found that fishing means more to the people of this community than food and jobs. Here in South Louisiana, fishing is a vital part of the vibrant local culture and community pride. In a region that’s been devastated by hurricanes and oil spills, fishing is also a source of something more important: hope.

Below, you’ll hear what fishing means to South Louisiana’s fishing communities through the voices of a former shrimper, the owner of a grocery store that has served the town of Chauvin for more than a century, and representatives of a local Native American tribe. You’ll also get a glimpse into this beautiful part of the world through a photo slideshow. Together, this paints a picture of communities that have overcome unimaginable struggle, but still look forward to the future, in no small part because of the riches of the sea.

Flotsam (what we’re obsessed with right now)

- This cuttlefish:

- Thanks to Nik Hubbard for bringing it to our attention.

Fog Horn (A Call to Action)

- #IAmSeaGrant. Despite being one of the most bipartisan research programs in the United States, with a huge return on investment for coastal communities and businesses, Sea Grant is under attack from the current administration. Deep Sea News has been collecting stories from marine researchers who’ve benefited from Sea Grant programs: Ben Wetherill, Nyssa Silbiger, and Christy Bowles.

- 27 National Monuments are under review by the Department of the Interior. Our Nation Monuments are our National Treasures. Don’t let them be sold to the highest bidder! Submit formal public comments on the DOI Monument Review and make your voice heard.

Flotsam (what we’re obsessed with right now)

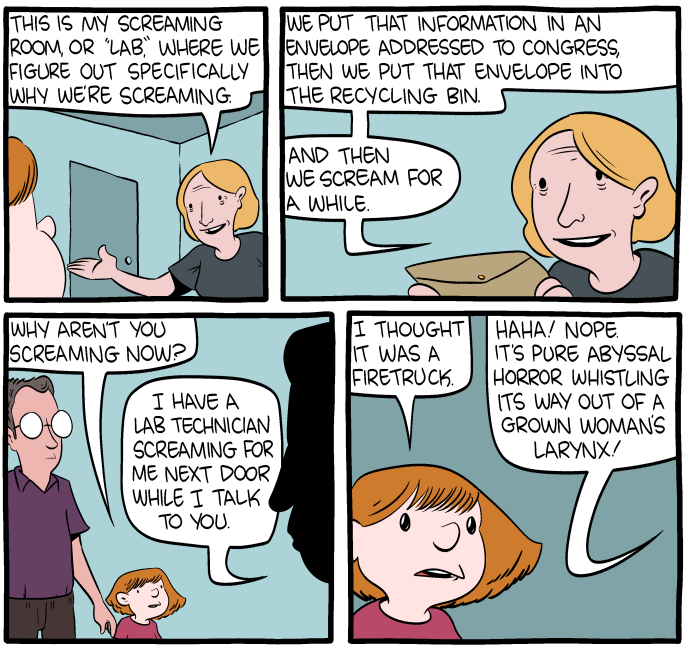

- Zach Weinersmith has perfectly capture the essence of what it is to be a marine biologist in the United States right now. Pure. Abyssal. Horror.

- The Deep Sea News crew is at sea, and Dr. Craig and his team did a hilarious, fascinating, informative Ask Me Anything over at Reddit. Worth reading the whole thread, even though it’s done for now.

As some of you probably remember, there was an oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico last year. You can be forgiven for not remembering it, as our news media hasn’t been talking about it very much lately. In fact, if your only source of oil spill news was the mainstream media, you probably think that the Gulf is doing great! A little over a year ago, CNN ran a story about how the BP oil well that caused the spill was “effectively dead” and was “no longer a threat to the Gulf”. CNBC (and many others) ran stories about how 75 percent of the oil from the spill was gone from the Gulf. Bloomberg reported that the Gulf would recovery completely by 2012. London’s Telegraph celebrated a dramatic recovery after only one year. Whew… things aren’t as bad as we feared, and the Gulf has almost totally recovered! Or has it?

As some of you probably remember, there was an oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico last year. You can be forgiven for not remembering it, as our news media hasn’t been talking about it very much lately. In fact, if your only source of oil spill news was the mainstream media, you probably think that the Gulf is doing great! A little over a year ago, CNN ran a story about how the BP oil well that caused the spill was “effectively dead” and was “no longer a threat to the Gulf”. CNBC (and many others) ran stories about how 75 percent of the oil from the spill was gone from the Gulf. Bloomberg reported that the Gulf would recovery completely by 2012. London’s Telegraph celebrated a dramatic recovery after only one year. Whew… things aren’t as bad as we feared, and the Gulf has almost totally recovered! Or has it?

The A-frame shuddered as the box core, heavy with mud and reeking of sulfur, emerged from the water. We knew that it had found its mark 2300 meters below. Soft sediment from the seafloor oozed out the sides as I slid the safety pins into the spade arm. There was nothing visibly special about this mud. No ancient arthropods or primeval polychaetes crawled through this muck. It was a cubic meter of sticky, stinking glop. My first sample.

We were in the middle of the Gulf of Mexico, aboard the R/V Cape Hatteras. Our cruise objectives were to characterize the pelagic and benthic fauna associated with deep-sea methane seeps. For me, it was a ship of opportunity. In exchange for and extra set of hands to work the gear and process samples, I could add my own small research project to the cruise objectives. My goal was to collect sediment cores from multiple sites and survey the diversity of fungi associated with these methane seeps.

The 12 hour shifts rarely left me enough time to eat meals. Though I had never seen the equipment before we left port I became the acoustic tracking technician, out of necessity. Things consistently went wrong. Nets tore, gear broke, a misfired box core almost crushed my leg. Two hurricanes, one a category 5, hit the Gulf of Mexico while we were at sea. Work was exhausting and rest was brief, when existent. I loved every minute of it.

The end of that cruise was the high point of a 4 year project that began with unbridled optimism and early, exciting results, only to decay into drudgery, failure, desperation, and collapse. In the end, it would rise from the past for one small victory. In hindsight, so much of those four years seems painfully trivial, but this story is really about how much of a human being is poured into a scientific manuscript.

Read More “The importance of failure in graduate student training” »