A longtime submariner I know tells the story of a most unusual dive. On this particular plunge, they went down into the briny deep to place what can best be described as a giant manhole cover on the seafloor. There was a hole, and, by all accounts, the sea was draining in to it.

For more than half-a-century, we’ve been drilling holes in the bottom of the sea. Some reveal the buried history of the evolution of our oceans. Others uncover vast wells of crude oil. Science, exploration, and exploitation have all benefited from ocean drilling programs. But what happens to the seafloor when you punch a hole in the ocean? In my friend’s case, the drilling program opened a sub-sea cavern, resulting in changes to local current regimes, potentially disturbing the surrounding benthic community. The most practical solution was to simply plug the hole.

We’ve punched a lot of holes in the seafloor, but despite a few anecdotes and scant research, we know precious little about how these holes actually alter the marine environment. This is particularly worrying, as deep-sea mining at hydrothermal vents, manganese nodule fields, and oceanic crusts are slowly creeping out of the realm of science fiction and into our oceans. Ocean drilling in the deep sea is perhaps the closest analog to industrial-scale deep-sea mining. Understanding the potential impacts is critical to designing management and mitigation regimes that protect the delicate deep seafloor.

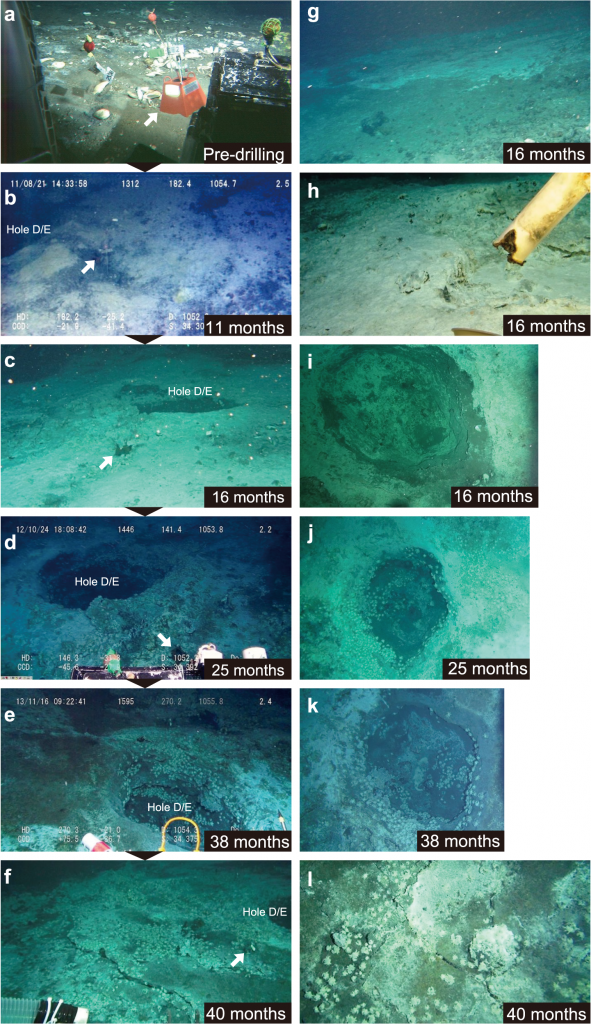

In perhaps the first study explicitly looking at the long term ecosystem effects of scientific drilling, Dr. Ryota Nakajima and friends surveyed a hydrothermal vent field over the course of three years following intensive drilling by the International Ocean Drilling Program. The seabed landscape of Iheya North Field, though dotted with hydrothermal vents and rocky outcroppings, is primarily a vast, muddy benthos. At drill site C0014, where the survey focused, a diffuse community of methane seep-dependent species–animals that rely on chemical energy that percolates slowly through the seafloor–scraped by. Colonies of the poetically-named clam, Calyptogenia, were the dominant large organism, and had been for at least ten years, though within those colonies, up to 90% of observed clam shells were dead.

The clam colonies were the first to go. Buried under the dense drill tailings–clay-like sediment from deep beneath the sea floor–the clams were effectively smothered.

That wasn’t the only change. The drill hole punctured many hard layers, layers that may have been acting as barriers, protecting the seafloor from subsurface heat sources. Eleven months after drilling, small hydrothermal vent chimneys began to form. The heat at some places was so intense that scientific instruments, placed to measure temperature and sedimentation rate, among other environmental conditions, melted. The fine grain, silty sediment (or, less technically, mud) which previously dominated the ecosystem, became hardened, so much so that 40 months after drilling, it was no longer possible to take a pushcore sample. These changes extended out up to 30 meters beyond the site of the original drill hole.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=djLBbe17OPU

Physical changes are followed by biological changes. Galatheid crabs and Alvinocaridid shrinp, species commonly associated with hydrothermal vents, settled on the nascent habitat. Predatory lithodids, giant spider crabs, occupied the perimeter. What had once been a muddy seafloor dominated by cold seep communities was now a full-fledged hydrothermal vent ecosystem. The changes appear to be permanent. This new vent system has so far persisted for over two years.

This is pretty huge. Drilling produces dramatic, profound changes in community composition, completely altering the ecosystem surrounding the drill hole, permanently. And while a drill hole is not a deep-sea mine, similar extractive processes are likely to yield similar results. When it comes the the newly formed, and not yet active, deep-sea mining industry, extreme caution must be taken to ensure that impacted ecosystems are not permanently altered.

So what happens when we punch a hole in the sea floor? In at least one instance, everything changes.

Update: After publishing this piece, we were made aware that despite containing nearly 700 words related to what happens when you punch a hole in the ocean, the author failed to include even a passing reference to Pacific Rim or anything resembling a Kaiju pun. We regret this oversight.

“Update: After publishing this piece, we were made aware that despite containing nearly 700 words related to what happens when you punch a hole in the ocean, the author failed to include even a passing reference to Pacific Rim or anything resembling a Kaiju pun. We regret this oversight.”

No Sesame Street reference, either. Just saying.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hYfJGxNH_SE