This week, I was invited to testify in front of Congress on the environmental and social impacts of deep-sea mining for the House Natural Resources Committee hearing Deep Dive: Examining the Regulatory and Statutory Barriers to Deep Sea Mining. In my opening statement, I touched on three critical points: the lack of urgency to access these deposits; the environmental impacts to the deep seafloor; and the lack of local support for deep-sea mining in the communities most directly effected by the industry.

You can watch the full hearing or and read my opening statement below.

Mr. Chairman, Madam Ranking Member, and Members, good afternoon and thank you for inviting me to speak today. My name is Andrew Thaler. I am a deep sea ecologist with more than 15 years of experience researching the environmental impacts of deep sea mining. My expertise includes deep sea ecology and marine technology.

My goal today is to give the Committee an objective overview of the reality of deep sea mining. While I have significant concerns about the long-term environmental harms that can result from mining the deep seafloor, I am not an absolutist against all forms of deep-sea mining. Polymetallic nodule mining in particular has promise. However, I do think there are significant environmental as well as practical hurdles that need to be addressed before any commercial mining is permitted.

While we frequently talk about deep-sea mining as a single cohesive industry, in reality it is three different industries targeting different ore types with wildly different impacts to the marine environment. Recent executive orders and RFIs take an inclusive approach to deep-sea mining permitting, so I think it is important to keep in mind that policies developed for polymetallic nodule mining will be inappropriate and insufficient for seafloor massive sulphide mining at hydrothermal vents or ferromanganese crust mining on seamounts.

In looking at the viability of a deep-sea mining project, I consider three overarching questions:

First, is it urgent? Given the current surpluses in the nickel and cobalt markets, the lack of domestic refining capacity within the United States, and the current pace of technological development, the urgency of deep-sea mining for polymetallic nodules does not exist. Current proposals involve a significant amount of stockpiling of nodules due to lack of refining capacity and the cheapest place to stockpile a nodule is to leave it on the seafloor.

Second, can it be conducted in a manner consistent with environmentally responsible best practices? For hydrothermal vents and seamounts, I do not believe that deep-sea mining is viable. These ecosystems are too small and too fragile. For polymetallic nodules, I remain optimistic that there exists a path forward that respects the ecosystems of the deep sea, but limitations to our knowledge of the long-term impacts and the evolving state of technology means that I am not yet confident that we have reached that point.

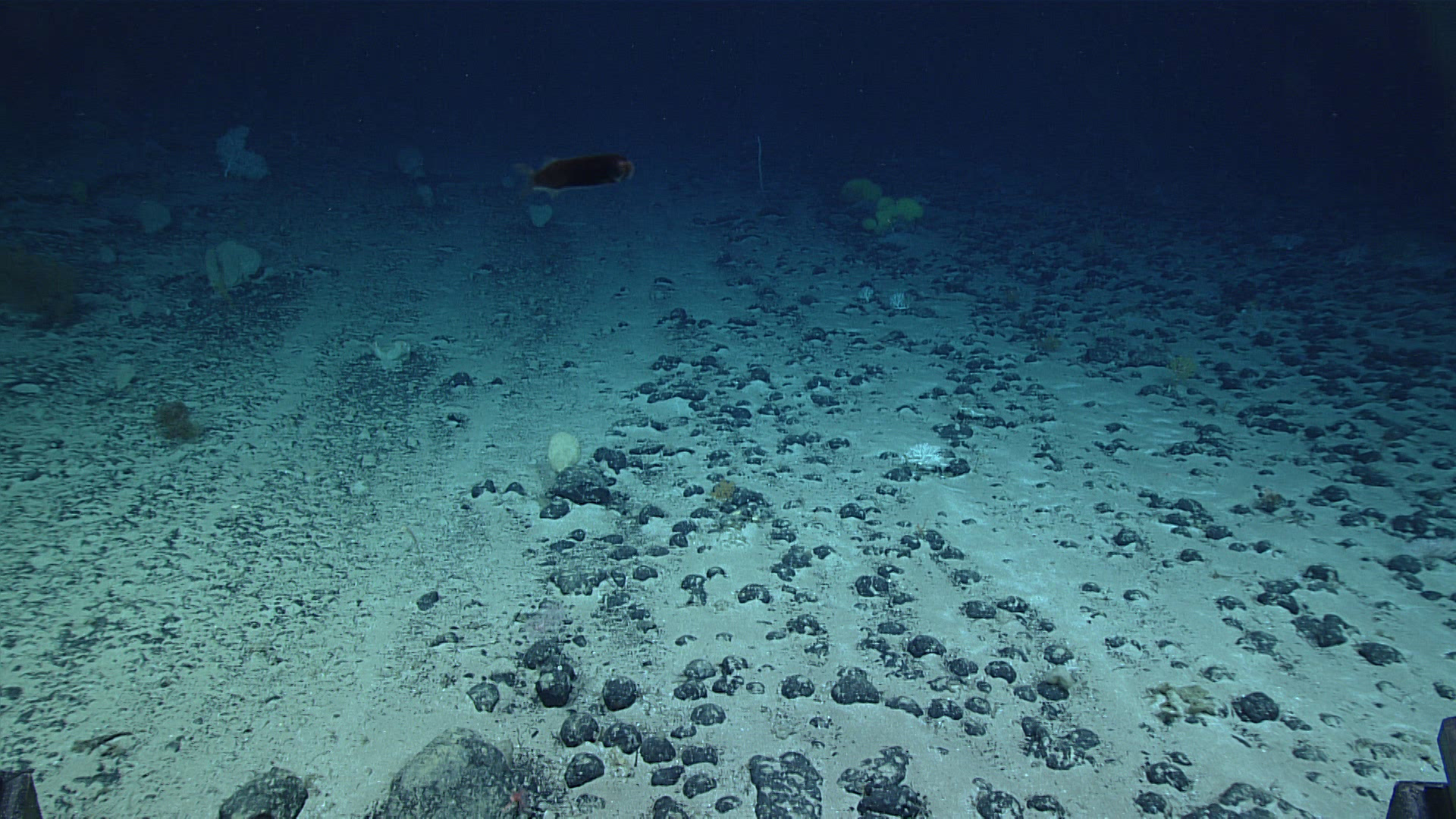

While my colleagues in the industry insist that the abyssal plain – the vast, flat areas of the ocean floor that lie 2 to 4 miles beneath the surface – is more akin to a desert than a rainforest, the opposite is true. The deep abyssal plain is more biodiverse than tropical rainforests, with more unique species and genetic novelty than almost any other ecosystem on the planet. High biodiversity coupled with low abundance of individuals makes these species especially vulnerable to extinction. Nodule fields provide unique habitat and species abundance within nodules fields can be two to three times higher than the background abyssal plain.

The direct impact to the seafloor from the mining tool and the benthic plumes which smother the area immediately surrounding extraction leave permanent scars, with species recovery still depressed decades after mining occurred. Nodule fields take millions of years to form and recovery occurs centuries. While I am supportive of the efforts undertaken by Mr. Barron and Mr. Gunasekara to address these impacts, ultimately, the science shows that we should consider any impact to the seafloor environment around a mining site to be permanent.

Beyond the seafloor, there are questions about the impact of mid-water and surface plumes that can spread chemically-polluted waters for hundreds to thousands of miles, impacting marine prey species as well as commercially important fish species. There is the production of marine noise, which persists throughout the lifetime of the mining operation. And there is the physical presence of ships in relatively untrafficked areas, which increase the risk of ship strikes to whales and other marine life.

Third, and, in my view, most important, does the project have local support? Within the US, mining will occur in areas connected to people with strong personal and cultural ties to these waters. Lack of local support has practical logistical impacts. A mining operation off the coast of American Samoa, will depend on American Samoan businesses and services. Without a good faith effort to build inroads in local communities, the realities of overseeing a large offshore operation become exponentially more challenging, expensive, and complex.

The responses to recent RFIs have revealed near-universal, bipartisan community opposition to deep-sea mining in American Samoa, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands. A rush towards commercial mining without first building significant relationships within these communities is unlikely to produce a successful venture. One only needs to look to offshore wind development in New Jersey to see how a lack of local support can hinder offshore development.

In international waters, there is an international community to address. Deep-sea mining is, by necessity, an international endeavor, and partner states such as Japan and Korea are party to the Convention on the Law of the Sea. Mining in the CCZ under US permits without the support of the ISA will lead to significant legal challenges, further slowing progress on the international mining code.

The lack of urgency, environmental unknowns, and local opposition does not justify a rush to expedite permitting for deep-sea mining. Deep-sea mining has many issues both environmental and practical that are still unresolved.

Thank you again for the opportunity to testify before this Subcommittee. I look forward to your questions.

Southern Fried Science is free and ad-free. Southern Fried Science and the OpenCTD project are supported by funding from our Patreon Subscribers. If you value these resources, please consider contributing a few dollars to help keep the servers running and the coffee flowing. We have stickers.