Learned scholars and respected leaders of society warn that a major environmental change is coming and everyone should prepare. However, heads of state, politicians and wealthy oligarchs argue and bicker, more interested in riches and power than the imminent threat. Some realize that the oncoming change will be accompanied by a host of problems, to which no one has given the necessary consideration. Those who understand the situation try to set up systems to protect against this threat but are constantly having to argue with, and even fight, their own allies. In the end, just as some progress is being made, one of the champions of these vital preparations is stabbed through the heart by his closest colleagues, who stage a coup instead of dealing with the oncoming threat.

Sound familiar? It is of course the plot of Game of Thrones, but could also be a history of most conservation issues, whether it be the threat of DDT, ozone depletion, biodiversity loss or climate change.

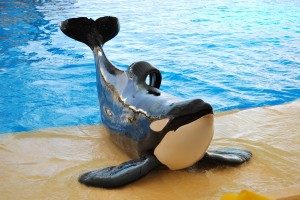

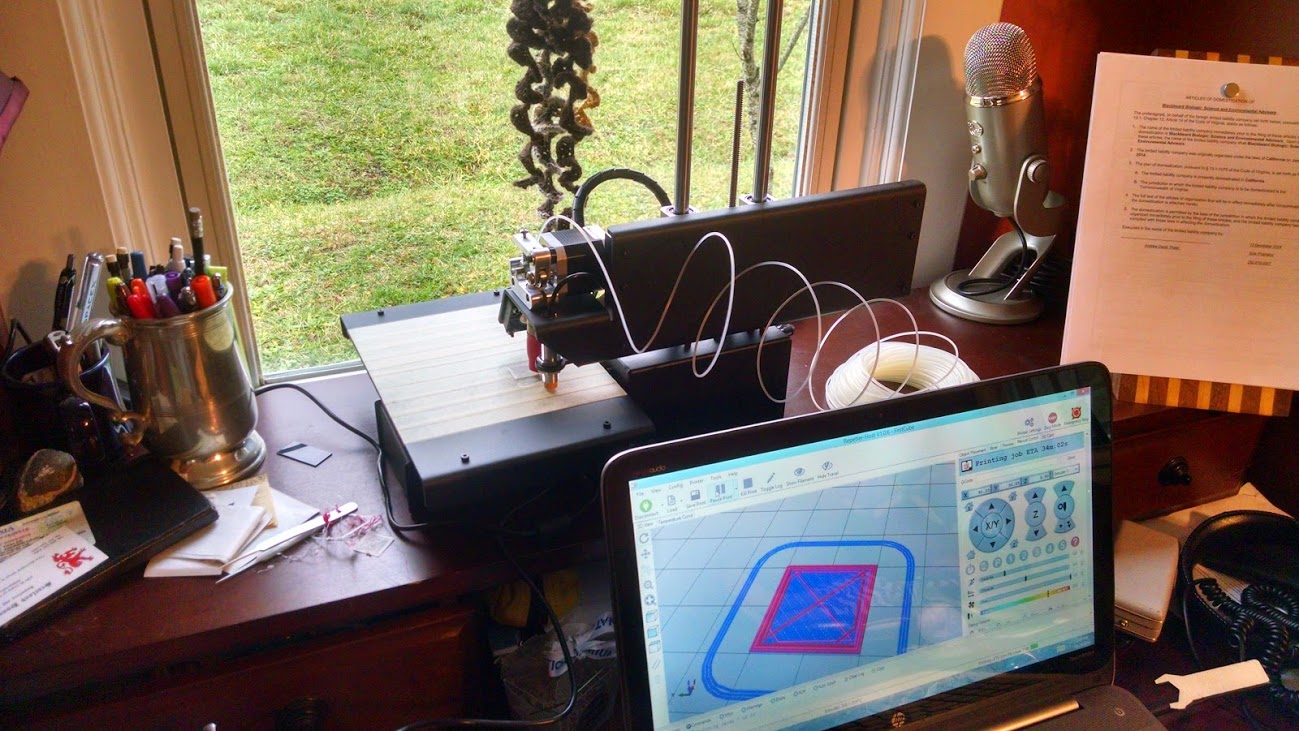

Joey Maier is a biology professor at Polk State College where he uses every possible opportunity to encourage his students to spend time in the water, play with technology, and do #CitizenScience. As an undergraduate, he did a stint as an intern for Mark Xitco and John Gory during their dolphin language experiments. He then spent the years of his M.Sc. at the University of Oklahoma thawing out and playing with bits of decaying dolphin. After discovering that computers lack that rotten-blubber smell, Joey became a UNIX sysadmin and later a CISSP security analyst.

Joey Maier is a biology professor at Polk State College where he uses every possible opportunity to encourage his students to spend time in the water, play with technology, and do #CitizenScience. As an undergraduate, he did a stint as an intern for Mark Xitco and John Gory during their dolphin language experiments. He then spent the years of his M.Sc. at the University of Oklahoma thawing out and playing with bits of decaying dolphin. After discovering that computers lack that rotten-blubber smell, Joey became a UNIX sysadmin and later a CISSP security analyst.