A new study breaks down the biomechanics of one of the marine world’s most unusual hunting behaviors.

Thresher sharks have one of the strangest body plans of any fish, with almost half their body comprised of a scythe-like tail. It had long been suspected that that they use this tail is a whip to stun aggregations of small bait fishes, a hypothesis supported by threshers entangled by their tails in fishing gear. It wasn’t until 2013 that this unusual hunting behavior was conclusively demonstrated. Watch it in action here. (When we joke to guests on the research vessel that most shark related injuries originate from the front, or “bitey end,” of the shark, thresher sharks are why we don’t say “all.”)

While this behavior has been long suspected and conclusively documented for a decade, we didn’t know how they did this… until now. What was unknown, and our motivation for this study, is the underlying structure that supports this extreme bending,” Jamie Knaub, a Ph.D. candidate at Florida Atlantic University and the lead author of a new study on thresher shark biomechanics. “We thought there might be something special happening in their vertebrae to support bending in both directions: swimming and tail whipping.”

Jamie Knaub in the lab with a thresher shark tail.

Answering this question required tools from the field of biomechanics. “In my field, we often talk about structure and function relationships: what does something look like and how does it work?” Dr. Marianne Porter, an Associate Professor at Florida Atlantic University and a coauthor on this study, told me. “The research my team does examines these relationships, and our goal is to understand how different animals are put together and how they move. As a scientist, I always get excited when I find tradeoffs among studied variables. Why does one measurement go up when the other goes down? I find it exciting to learn about all the nuances of life.”

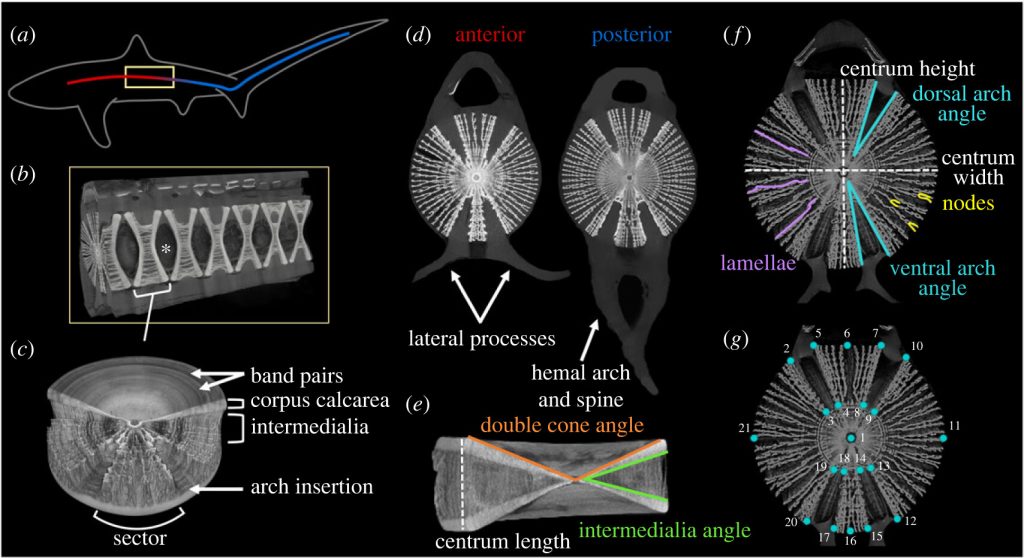

Figure 2 from Knaub et al. 2024: Thresher shark vertebral macro- and microstructure. (a) Whole body diagram of a vertebral column (gradient line) within a thresher shark. Vertebrae are cylindrical and a consecutive section outlined in yellow is shown in (b). (b) Cutaway of vertebrae; the frontmost is the transverse midplane section displaying the four sectors of radiating lamellae and gaps in mineralization for the arch insertions. Centra are separated by an intervertebral joint (an example joint is depicted by an asterisk). (c) Three-quarter view of whole centrum; band pairs are visible on the dorsal centrum face. A cutout displays lamellae radiating from the centre of the centrum and forming the intermedialia that stretches between the corpus calcarea (double cone structure). (d) Transverse view of thresher shark anterior and posterior body vertebrae along the vertebral column. In anterior body vertebrae, lateral processes project outwards, whereas posterior body vertebrae have a hemal arch and spine that project ventrally. (e,f) Morphometrics and mineral architecture measured. A sagittal and transverse cross section showing variables quantified: centrum height, width, and length, lamellae count, node count, dorsal and ventral arch angles, intermedialia angles, and double cone angles. (g) Transverse cross section showing 21 digitized landmarks (points in cyan, labels in white) used for geometric morphometric analysis.

To analyze the biomechanics of thresher shark vertebral columns, Knaub and her team compared vertebrae from different parts of the spinal column in thresher sharks of all sizes. “We found that the anatomy of the vertebrae is different in the front compared to the back, both in the type and amount of structures present,” Knaub told me. “Based on what we know about shark vertebrae, we think the differing anatomy helps thresher sharks perform tail-whipping by stabilizing the main body and allowing the back end to be more flexible. This makes sense when you think about the whipping behavior as a catapult. Catapults have a sturdy beam (the shark’s main body) and a flexible sling (the base of the tail) to throw an object (the tail) overhead. We also found that the structures in the vertebrae increase with body size, so we think as thresher sharks grow, they may need more structural support in their vertebrae to be able to whip a larger tail.”

Knaub in the lab analyzing thresher shark vertebrae

This study helps to explain a weird shark behavior while adding to our growing knowledge of how sharks do the amazing things that they do. “We don’t fully understand shark skeletons, so our study is useful in grasping a better concept of mineralized cartilage form and function and how it may adapt to specific behaviors, like tail-whipping,” Knaub said. “Now that we have a greater understanding of vertebral anatomy in thresher sharks, we can look to other species and make anatomical comparisons in relation to their behaviors and ecology.”

I reckon their eye anatomy is different too? Dr. Castro once mentioned the weird way they turn their eyeballs back in their heads to look backwards, presumably to better see their whippy tails in action.