- Election of ISA Secretary-General mired by accusations of bribery and corruption

- International Seabed Authority gears up for a leadership challenge at the July meeting.

- No, the ship didn’t steer towards the pylon: A brief fact check on the MV Dali collision with Baltimore’s Key Bridge

- New Deep-sea Mining Bill Introduced in Congress

- NOAA confirms North Atlantic Right Whale killed by commercial lobster gear

- Norway moves one step closer to deep-sea mining

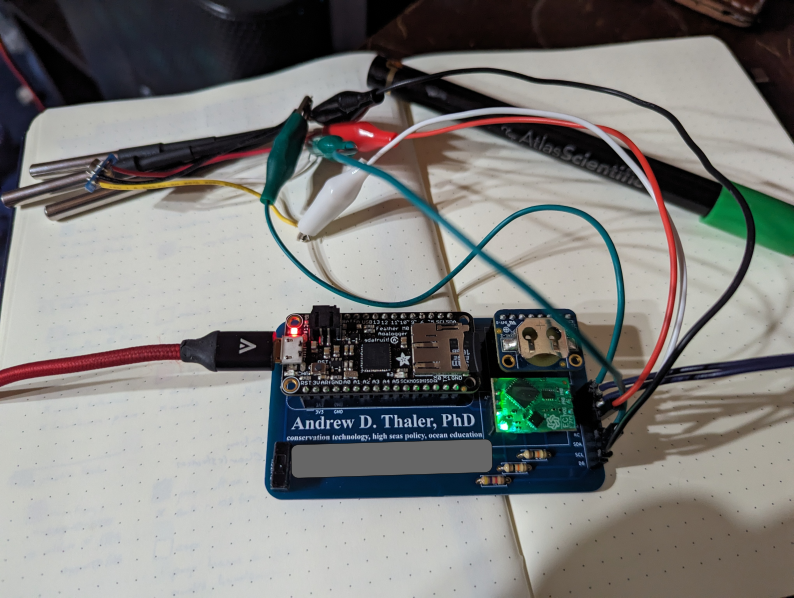

I spend a lot of time talking about the OpenCTD, my important, gigantic electronics project aimed at making the foundational tool of oceanography available to those most directly affected by our changing oceans. It’s been a minute since I’ve written about any of my weird little electronics projects. I do lots of weird little electronics … Read More “A calling card for oceanographers” »

On Monday, the venerable, Beyoncé-endorsed seafood chain declared bankruptcy. Red Lobster has been struggling for a while. It was sold to private equity firm Golden Gate Capital in 2014 for $2.1 billion and then bought out by the seafood supplier Thai Union in 2020. Thai Union is one of the world’s largest seafood conglomerates. Thai … Read More “You did not bankrupt Red Lobster by eating too many shrimp.” »

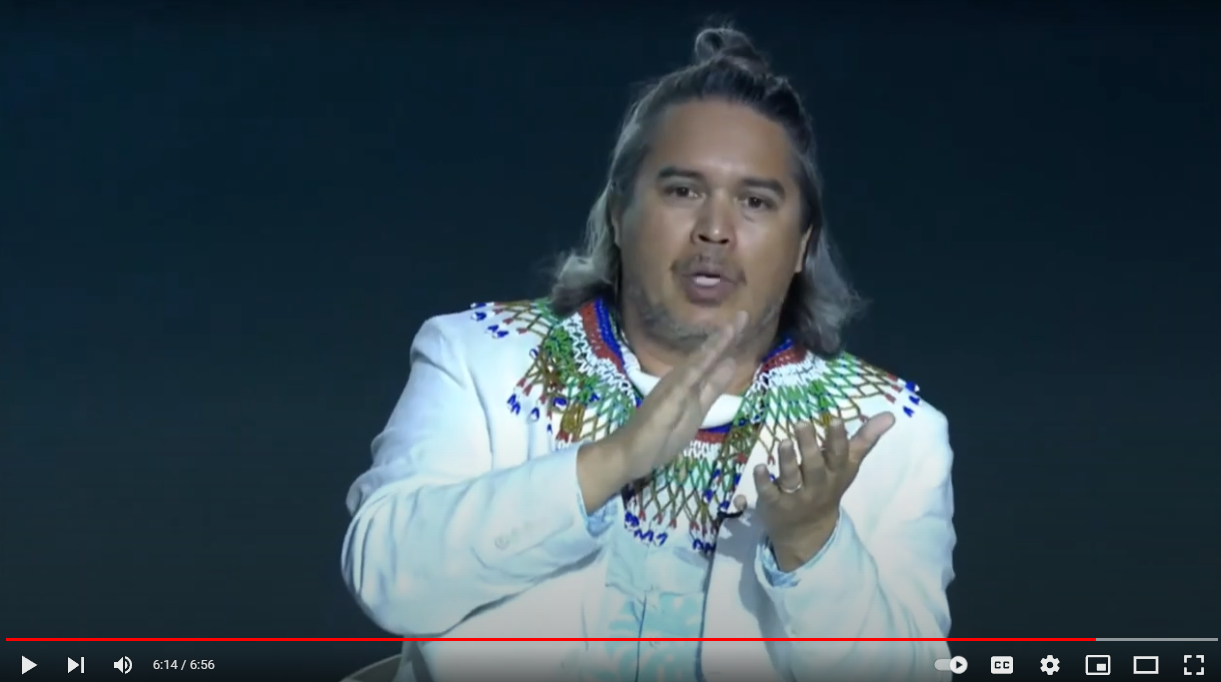

We’ve got a pair of great podcasts featuring the Southern Fried Science teams this week, starting with Angelo Villagomez on How to Protect the Ocean talking about marine protection, 30×30, and lessons learned from a lifetime protecting the ocean. Longtime friend of the blog, Beth Pike, also joins in. If you want to take a … Read More ““When you fail, you learn” and Live at AwesomeCon 2024!” »

The world’s leading sustainable seafood certification standard just made some big changes for sharks

Here are what the Marine Stewardship Council’s new requirements for sharks caught in certified sustainable fisheries mean. Sharks and their relatives are some of the most threatened vertebrates on Earth, and the number one threat by far is unsustainable overfishing practices. The Marine Stewardship Council, the non-profit that runs the world’s largest sustainable seafood certification … Read More “The world’s leading sustainable seafood certification standard just made some big changes for sharks” »

The International Seabed Authority is the regulatory body that oversees deep-sea mining in areas beyond national jurisdiction – they’re tasked with develop the mineral resources of the high seas seabed while protecting the marine environment. At the heart of the ISA is the Secretariat, the administrative organ charged with the day-to-day operation of the ISA. … Read More “International Seabed Authority gears up for a leadership challenge at the July meeting.” »

What if you could drop an oceanography lab anywhere? Not just the instruments and equipment, but the expertise to maintain the equipment and train ocean knowledge seekers. What if you could deliver an instrumentation factory anywhere it is needed, so that people with the desire and need to study and understand the ocean had the … Read More “Independent ocean science requires local support: testing our mobile OpenCTD factory.” »

Ten years ago, freshly married and freshly relocated to Vallejo, California, I found myself in the midst of reinvention. The cycle of post-doctoral fellowships and short-term contracts necessary for an academic career didn’t suit me. I wanted stability and, importantly, I wanted freedom. Crowdfunding was new. Earlier that summer, OpenROV had shook the crowdfunding world … Read More “Small drops make mighty oceans: 10 years as a scientist on Patreon” »

April was a slow month. Most of our lead writers were tied up with classes, workshops, and other projects and we only managed to publish 6 articles this month. That’s about a third of our regular output. On top of that, we had a server outage that took us offline for a a few days. … Read More “You probably don’t want to work for me: What you read on Southern Fried Science in April” »

Last week, Angelo spoke at thew 2024 Our Ocean Conference in Greece about going beyond 30×30 and how we equitably measure ocean success. You can also read his full prepared statement here: What I Meant to Say at Our Ocean Greece 2024

Canadian Masters students will now get up to $27,500 CAD a year, up from $17,500. Ph.D. students will get up to $40,000 CAD a year, up from as low as $20,000. Here’s how the leaders of Support Our Science did it. The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length. DS: Why was … Read More “Canadian grad students won their first raise in 20 years. Here’s how Support Our Science made it happen.” »