Transcript available below.

Tag: drones

Foghorn (A Call to Action!)

- Melissa Márquez is fundraising to participate in a women-in-science leadership retreat that culminates in a 2.5 week trip to Antarctica. Help her out! Or back her Patreon!

- The scandal-plagued, utterly ineffective, Scott Pruitt is out, just days after an American patriot told him exactly how she felt about him in a restaurant. Good.

Flotsam (what we’re obsessed with right now)

- Investing in indigenous communities is most efficient way to protect forests, report finds. This should surprise no one but it often does.

- Explore the deep waters around Kiribati with OpenExplorer!

The Levee (A featured project that emerged from Oceandotcomm)

- Virtual Reality Preserves Disappearing Land: Coastal communities are capturing their cultures and landscapes in virtual reality before sea level rise steals them for good.

- Where Did the Oil Go In the Gulf of Mexico? a storymap.

We’re late because Andrew doesn’t understand time zones.

Foghorn (A Call to Action!)

- This is an incredible oportunity for an early career researcher to get their feet wet leading a deep-sea science cruise: Announcing a NSF-UNOLS Early Career Training Cruise Opportunity to the East Pacific Rise 9° 50’N – December 2018

Flotsam (what we’re obsessed with right now)

- We have a new writer! Please welcome the Original Saipan Blogger, Bucky Villagomez!

- Hafa Adai from the Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas Islands! Are you following along with our adventure on OpenExplorer? Yesterday was one of the highlights of my career: Marine Ecology and Underwater Robotics in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.

- Add this to the list of things that are really not good: Atlantic Ocean Current Slows Down To 1,000-Year Low, Studies Show.

- Look, if anyone could actually pull this off, it’s Phil Nuytten, but I. Have. Questions: Who’d like to live under the sea? H/T to Dr. Diva Amon.

The Levee (A featured project that emerged from Oceandotcomm)

- Behold, the interactive Salt Marsh!

- David S. and S. David did a thing!

Fog Horn (A Call to Action)

- Hakai Magazine want to hear from you! Dear Hakai Magazine Reader, Who Are You?

Flotsam (what we’re obsessed with right now)

- Everything Tangier is utterly fascinating right now: Angry messages to the Trump-supporting mayor of Tangier Island illustrate a need to listen, not to shout.

- I’m still just dumbfounded by this: Did a Glowing Sea Creature Help Push the U.S. Into the Vietnam War? In other words, Ocean Literacy could save us all from annihilation.

- I really hope you’re not sick of hagfish yet. Because Hagfish!

- Best headline, ever: Sea Spiders Pump Blood With Their Guts, Not Their Hearts.

Welcome to 2017 and the ninth year of marine science and conservation at Southern Fried Science!

Flotsam (what we’re obsessed with right now)

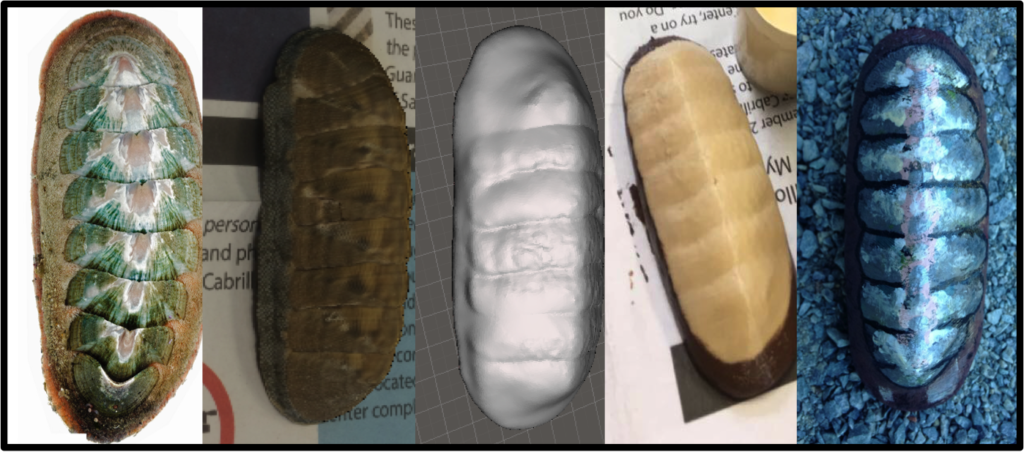

- Alex Warneke knows exactly how to push all of my ocean outreach buttons: Low-cost teaching tools? Check! Hands on student engagement? Check! Open-source materials and datasets? Check! 3D Printing? Check! Meet 3D Cabrillo:

- Learn more about this awesome project from the National Park Service: How to Build a Better Biomodel.

Jetsam (what we’re enjoying from around the web)

It’s nearly summer, which means the shores will soon be filled with SUP boards, drones, and self-professed whale whisperers. This authentic lifestyle is an obnoxious time for marine mammals, and soon your online feeds will be flooded with aerial footage of people “sharing the water” with marine megafauna. Some of these shots are innocent but an … Read More “Learn what whale harassment looks like (GIFs)” »

Two years ago, I moved to San Francisco. It was… an experience. I had the opportunity to meet some incredible technologists, leaders in the emerging world of citizen exploration, and developers, coders, and makers using their skills and expertise to help save the environment. I met some amazing drone builders developing platforms and tools to measure the world. I also learned that West Coast living was not for me. The southern Atlantic coast called me back. But before I left, I led a small team across the Pacific to Papua New Guinea, where we taught undergraduates from the University of Papua New Guinea and the University of the South Pacific how to build and operate OpenROVs and incorporate them into marine ecology research.

Two years ago, I moved to San Francisco. It was… an experience. I had the opportunity to meet some incredible technologists, leaders in the emerging world of citizen exploration, and developers, coders, and makers using their skills and expertise to help save the environment. I met some amazing drone builders developing platforms and tools to measure the world. I also learned that West Coast living was not for me. The southern Atlantic coast called me back. But before I left, I led a small team across the Pacific to Papua New Guinea, where we taught undergraduates from the University of Papua New Guinea and the University of the South Pacific how to build and operate OpenROVs and incorporate them into marine ecology research.

The West Coast was good to me. It helped refine my vision for bringing low-cost, open-source technologies into the marine science and conservation world. Citizen science is becoming increasingly important, and the need for both democratizing and decolonizing science will drive much of the evolution of the scientific community in the 21st century. Tools that are effective, cheap, and open-source will play a major role in this transition. I returned east and began planning the next phase of this vision.

The Chesapeake Bay (San Franciscans take heed, you can keep your “Area” but “The Bay” will always be the Chesapeake) is the largest estuary in the United States, is economically important for shipping, fisheries, and tourism, and also happens to be the body of water that I grew up on. I learned to swim, fish, sail, and motor in one of the Bay’s many tributaries. It’s also home to more than a dozen research institutes, which work, sometimes in coordination and sometimes not, on studying and protecting the Bay.

Read More “From Sea and Sky: Hacking the Chesapeake with #BayBots” »

I submitted the following to the FAA regarding docket number FAA-2015-0150: Operation and Certification of Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems. Comments can be filed online, but I also sent an actual, physical letter. If you care about the regulation of drone in US airspace, you have until April 24, 2015 to submit you own.

I am a marine ecologist based in Virginia, with plans to operate small Unmanned Aircraft Systems in the conduct of marine ecologic research.

With regards to the FAA’s recently proposed regulations for the Operation and Certification of Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems, I find that the vast majority of suggested restrictions and requirements to be both reasonable and not particularly onerous for those wishing to operate UAS’s for commercial purposes. I commend the FAA for taking a pragmatic approach to UAS regulation. In particular, I support the requirement for a comprehensive knowledge test, which will be separate from and less expensive than a full pilot’s license. I also appreciate the recognition that UAS technology is advancing so quickly that a certification of airworthiness for specific airframes will place an undue burden on commercial pilots and force them to operate vehicles several generation behind the state of the art. I also approve of a special exemption for “microdrones”, which have significantly a lower safety risk and allow UAS pilots additional freedom in their use of very small vehicles.

I approve of the requirement that operators maintain visual line-of-sight, however, in the proposed regulations, there are make no provisions for autonomous flight. Autonomous flight dramatically changes the relationship between the aircraft and the operator and is an essential component of ecological surveys, allowing drones to fly straight transects and pinpoint sampling sites. This points to a more specific problem with the proposed regulations: in current form, there is little clarity regarding the role of scientists and other researcher in relation to UAS use. Will ecologists fall under the same restrictions as commercial drone pilots, or will they be treated more similar to hobbyist?

I urge the FAA to adopt a “Science Flyer” certification, similar to the American Association of Underwater Scientists “Science Diver” program. To wit, science divers have enhanced training requirements over recreational SCUBA divers, but less than professional commercial divers. A Science Flyer program could span a similar gap, with more training requirements than a hobbyist but fewer restrictions than a commercial UAS operator and could also provide additional training and certification to allow for autonomous operation.

Read More “Science Flyers: My comment to the FAA regarding proposed new drone regulations.” »

This weekend, the FAA released its proposed rules regulating the use of small Unmanned Aircraft Systems (drones). Today, I worked through the full, 200-page document, so that you don’t have to. These regulations, which are 3 years in the making and soon to be open for public comment, would determine who could fly, what licensing is required, and what limits would be imposed on drone flights. The regulations are pretty fair and leave open plenty of room for amateur enthusiasts while charting a way forward for commercial operators, but there are some glaring oversights and some unnecessary (and ineffective) security steps. I’ve written extensively on the used of drones for marine science, so my big question is: How will these rules impact drone use for research and conservation?

Before I get into specific research and conservation applications, here is my general impression of this proposal. Overall, I think it’s good. Most of the suggestions are reasonable and not unnecessarily onerous. I particularly like that there could be a special exemption for microdrones, so your tiny Hubsan x4 wouldn’t be treated like the massive and mighty Aerotestra IVAN. I’m a big proponent of ensuring drone operators have the proper knowledge base, so I actually like the requirement for a comprehensive knowledge test, which will be separate from and less expensive than a full pilot’s license. I like that there’s no requirement to certify the “airworthiness” of drones as if they were 6000+ pound aircraft (the certification process take 3 to 5 years and drone tech moves so fast that by the time one was certified, it would be several generations obsolete).

Read More “How will the FAA’s proposed rules impact drone use for research and conservation?” »

Over the last few months, I’ve been digging into the confusing tangle of laws that protect marine mammals and regulate the use of drones–small, semi-autonomous vehicles used by both researchers and hobbyists to observe whales and other marine mammals. You can check out the outcome of my findings over at Motherboard, where I just published Drones Would Revolutionize Oceanic Conservation, If They Weren’t Illegal. The quick and dirt summary is that there is no legal way to fly drones near whales, at the moment, but there are ways to do it responsibly while we work to catch regulations up with technology.

In working through these guidelines, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about how we can use this new technology to aid ocean conservation. Below are my top 10 favorite ideas for using drones to save the ocean.

1. Monitor our coastlines for poaching and other illegal activities.